Established 1982, Richmond CA

NIAD is the smallest of the three programs in the Bay Area started by Katz, serving 60 clients (about 30 at a time). It’s located in Richmond, a district in the Northwest corner of San Francisco, which is fair to describe as “out of the way”. NIAD, Creativity Explored, and Creative Growth all made location decisions many years ago that have proven to be very significant. CE rents in the hip Mission District, accessing valuable foot traffic for the gallery. In exchange for being remotely situated, NIAD owns a beautiful building that presents their program excellently (Creative Growth both owns a great building and is in a great location).

NIAD’s studio structure fits the standard model developed by these Bay Area programs - an open studio overseen by a team of teachers, each specialized in a particular media. The studio is separated into stations, with an amorphous system for determining who works where at what time. Generally, clients are encouraged to alternate stations and have the opportunity to learn a variety of methods.

NIAD also uses a tier system to denote where each artist is situated professionally, although it’s not as rigidly structured or administered as others. Timothy Buckwalter, the program’s enthusiastic Director of Exhibitions and Marketing, uses a baseball analogy to describe their tier system: artists are categorized as Major League, Minor League, or Recreational. Recreational tier artists participate primarily for socialization and leisure, Minor League artists take their work seriously and strive for creative careers but aren't fully developed yet, and Major League artists are mature, committed artists with well-established voices and practices.

Painting by Sarah Malpass

We met with Timothy Buckwalter, which was supplemented by discussions with a few of the teaching staff. We weren’t able to speak with Deborah Dyer, the program’s Executive Director. Based on this we can interpret that NIAD is excited about promoting a contemporary studio and gallery, but perhaps isn’t as concerned with service provider ideology or philosophy - for them, these ideas are entrenched in the program’s history and established in the program’s culture.

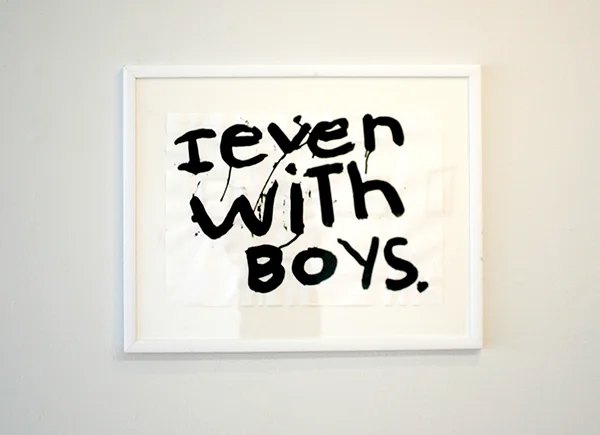

A sense of the program’s ideas is well articulated, though, by the gallery space. When we arrived, Buckwalter was busy installing What Are Words For: The Language Pieces of Sara Malpass. The show included three distinct bodies of work from Malpass – hand-written lists on notebook paper, text paintings, and ceramic sculptures depicting Sara’s words. The simple list works are clearly the purest; Malpass had been making these prior to NIAD or any exposure to art-making. This could arguably be understood as her “outsider” work. The paintings appear to be the result of teaching and exposure to new media and ideas in the studio and they effectively demonstrate how this kind of support allows an artist like Malpass to develop her body of work. The ceramic works are a step further removed. They’re traced from text paintings by a studio assistant and could possibly be described as experiments invented to expand the range of her voice (passively permitted by Malpass into her oeuvre) rather than actively devised and manifested independently.

Ceramic Works by Sarah Malpass

An important philosophical conflict emerges here. A purist, true to the original concept of programs facilitating artists, would only approve of the list works on paper. If this purist idea is largely based on making the point that these artists don’t need any outside influence to be great, then it’s flawed, because these artists deserve as much outside influence, support, and opportunity to benefit from learning as any other artist. The most appropriate kind of support tends to occur naturally when teaching artists spend time with the client artist and inevitably develop a peer relationship. Through this relationship, they learn to understand their student and enable them, rather than simply trying to improve their work. A program must make a distinction between art that’s devised by a teacher or collaboratively with a teacher based on a thorough understanding of the students’ independent concepts and intentions in order to maintain a well-defined line between the artist’s work and products based on their work.

NIAD is looking for ways to expose their artists’ work to a larger audience. Although their exhibition openings tend to be very successful and well-attended, they don’t have the benefit of regular foot traffic that their counterparts do elsewhere.

Just recently, they premiered an “affordable art online” exhibition series, a weekly website feature; a guest curator organizes a collection of works from their large catalog to be available for sale online ( check it out here).

A compelling and unique practice that NIAD has implemented is exhibiting work by artists outside of the served population explicitly for the benefit of the studio artists. This is an excellent example of new integration methods that are integral and unique to Progressive Art Studios. It exposes NIAD’s artists to contemporary art that may echo their own processes, while allowing them to recognize themselves as part of a larger professional community. Re-defining community integration to include these ideas is absolutely crucial for the future of these programs. Supporters of this population (especially of initiatives like Employment First) tend to have an oversimplified understanding of integration to mean working in the same physical space as others who don’t live with disabilities. Practices like this demonstrate that integration, understood more thoughtfully, can result in a much more beneficial and meaningful experience.