Bad Bon Squared, 2012, acrylic on paper, 16" x 24"

...All the Ones Bon Has Killed, 2013, acrylic on paper, 16" x 20"

Mischief in the Ladies Room, 2012, acrylic on paper, 16" x 24.5"

Larry Pearsall is a Los Angeles-based artist who has created an extensive, focused body of work at ECF’s downtown studio for over a decade. Pearsall's paintings have a masterful quality, which can be difficult to access only because of their strangeness and ambiguity; the more his epic narrative is given weight or trusted, the more unsettling it becomes.

This conflict between endearing and repelling the viewer is one that Roger Ebert struggled with for years in his evaluations of David Lynch’s films. In 1986 Ebert published an infamously critical review of Blue Velvet in which he wrote:

"Blue Velvet" contains scenes of such raw emotional energy that it's easy to understand why some critics have hailed it as a masterpiece. A film this painful and wounding has to be given special consideration. And yet those very scenes of stark sexual despair are the tipoff to what's wrong with the movie. They're so strong that they deserve to be in a movie that is sincere, honest and true. But "Blue Velvet" surrounds them with a story that's marred by sophomoric satire and cheap shots. The director is either denying the strength of his material or trying to defuse it by pretending it's all part of a campy in-joke.

The critical failure of this analysis was most overtly manifest in his conclusion that Lynch’s 1950s sitcom-informed idealization of suburban middle america was intended to be a cynical, insincere mockery. Presuming this was “sophomoric” social commentary he quipped, “What are we being told? That beneath the surface of Small Town, U.S.A., passions run dark and dangerous? Don't stop the presses.”

For years, even as Lynch continued to push and perfect his particular brand of idealism in Twin Peaks, Ebert couldn't conceive of Lynch’s sincerity because of a preconceived expectation that the process of storytelling is a means to an end, whose product for the viewer is the first and only priority.

For over a decade, Ebert would continue to respond to Lynch’s work with criticism and poor ratings that featured the same conflicted fascination, praising Lynch’s craftsmanship and the “power” of his films, yet lamenting that over multiple viewings he “tried to like them”, but was persistently repulsed. Four years later, in his two star review of Lynch’s Wild at Heart he admits:

There is something inside of me that resists the films of David Lynch. I am aware of it, I admit to it, but I cannot think my way around it. I sit and watch his films and am aware of his energy, his visual flair, his flashes of wit. But as the movie rolls along, something grows inside of me - an indignation, an unwillingness, a resistance.

And again in his 1997 review of Lost Highway:

Lynch is such a talented director. Why does he pull the rug out from under his own films? I have nothing against movies of mystery, deception and puzzlement. It's just that I'd like to think the director has an idea, a purpose, an overview, beyond the arbitrary manipulation of plot elements. He knows how to put effective images on the screen, and how to use a soundtrack to create mood, but at the end of the film, our hand closes on empty air.

The internal conflict of fascination and repulsion that Ebert passively reveals in accusing Lynch of “denying the strength of his own material” is important to evaluate in understanding the work of Larry Pearsall. Like Lynch, he is wont to idealize romantic notions of the world, while faithfully following the honest impulse to evoke an unsettling depiction of that which is unsafe or disturbing.

Ebert overlooked the possibility of the storyteller prioritizing process over its product, intending to employ the means and devices of narrative for the sake of exploration without necessarily moving toward a known resolution. He didn't imagine that the antipodal elements of Lynch’s films could be conceived not in order to create a contrast for the viewer to interpret, but solely as advisories within a highly personal method of exploring complicated and enigmatic ideas.

In the same way, understanding the paintings of Pearsall requires that we position ourselves not as receivers of a story, but observers of its telling - leaving behind our expectation for resolution or cohesion, and instead witnessing the mysterious narrative from a perspective parallel to the storyteller, considering the dark and romantic elements as explorations of those ideas and their relationships to each other.

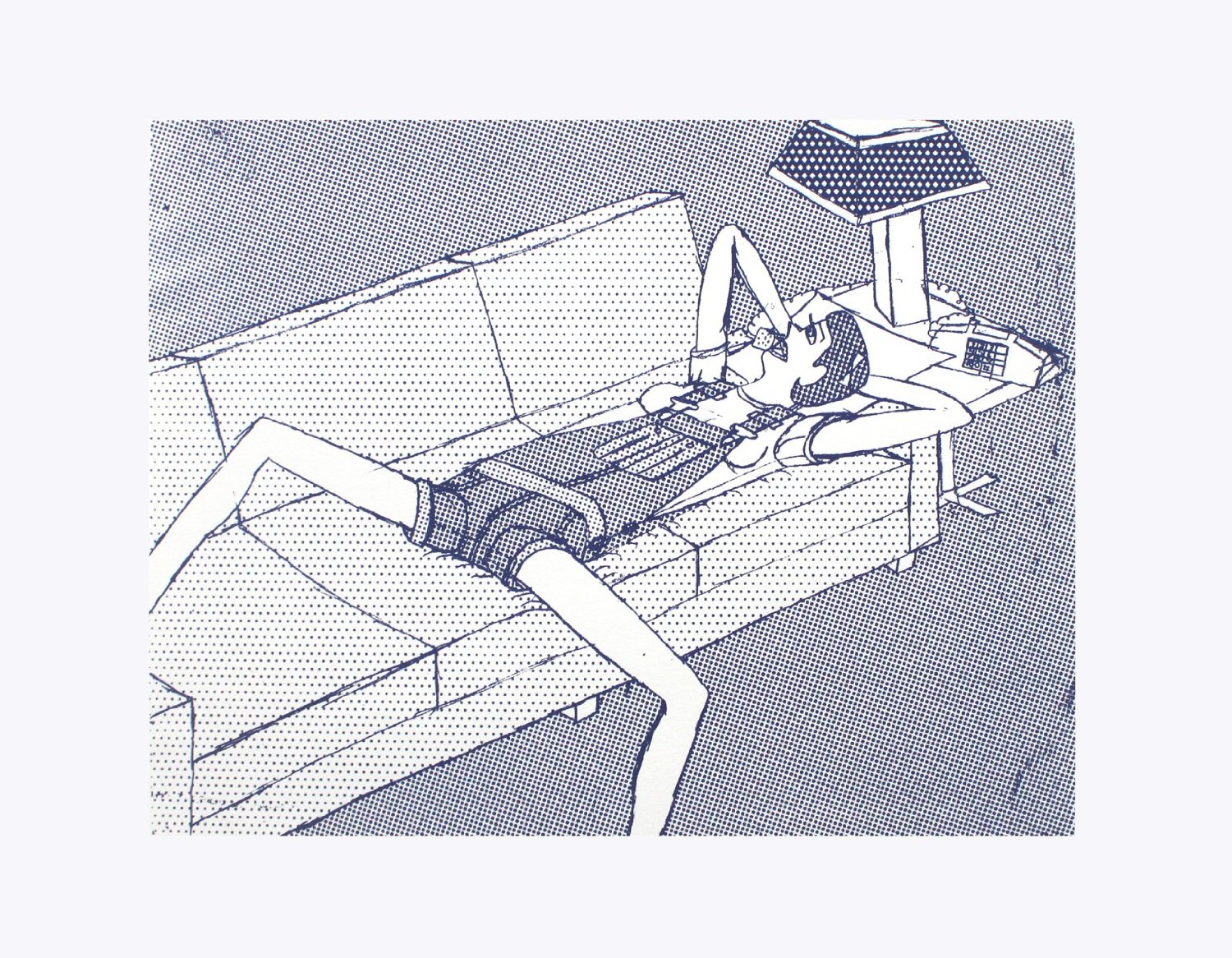

The Phone Call, 2014, screenprint, 11" x14"

When Pearsall discusses his work, there’s no doubt that he has very specific intentions and process is central to his oeuvre - part of him always remains engaged with developing the singular world of Apple Bay, the setting in which his remarkable vision is realized.

Apple Bay is big city, he says, like Los Angeles or New York, with many neighborhoods. Within the city “the old man” (a murderous, bearded pedophile named Bon) keeps children imprisoned in a dark, abandoned warehouse, a group of prepubescent “guys” called “the Overall Team Club” congregate, a pack of cats pose an unclear threat to Bon, and demons are pervasive. When Pearsall explains this sprawling world, he quickly gets caught up in detailing its many non-linear stories. It's clear that nothing is resolved; the conflict of good against evil is ongoing and not entirely within his control. He describes Apple Bay as a place “where good and bad things happen.”

In a recent conversation, Pearsall elaborates on the role conflict plays in his work:

Technically, Pearsall’s acrylic works on paper are clearly reminiscent of comic book imagery. His flat, illustrative approach is highly systematic, describing blocky three-dimensional space populated by figures with distinctly jointed limbs and deliberate facial expressions that are situated in stiff, action figure poses.

Although this methodical visual language creates a world that could be found in a graphic novel, it's not one entirely simplistic or stylized; there’s an intense reality in Apple Bay’s minute details - armpit stains, shifting tones of bathroom tile grout, narrowing brick mortar lines where a spotlight shines more brightly, or the particular mirror reflection in Mischief in the Ladies Room. These moments are included not because they particularly matter visually, but because the light and air that moves through the city is authentic - choices that result from Pearsall’s principled and devoted interest in discovering the truth within the complex, ongoing narrative of Apple Bay.

Larry Pearsall is represented by DAC Gallery in LA. He has exhibited extensively with DAC and was included in Storytellers, our recent curatorial project at LAND in Brooklyn.

Billy Got Knocked Out By Ray Thump, 2013, acrylic on paper, 16" x 20"