Marlon Mullen’s second solo exhibition at JTT Gallery is an expansive collection of recent works by this San Francisco-based hero in the progressive art studio movement.

Read MoreDisabled Artists Show Us a Way Forward Against a Trump Adminstration

The rise of Donald Trump over the past year has been for us, like many, a growing dread - not wanting to believe that America would really elect an unfit candidate, while watching both political parties and the news media self-destruct in the face of a changing world....

Read MoreMapping Fictions: Daniel Green

Daniel Green, Fifteen People, 2009, Mixed media on wood, 14.25 x 22.5 x 1.75 inches

Daniel Green, Little Mac vs Soda Poponski, 2015, mixed media on wood, 11.5 x 15 inches

Daniel Green, The Sun, 2015, mixed media on wood, 6 x 16.5 x 1 inch

Daniel Green, Business Delivery, 2011, Mixed media on wood, 13 x 29 x 1 inches

Daniel Green's process is slow and intimate; quietly hunched over his works in the bustling studio, he draws and writes at a measured pace. These detailed works are an uninhibited visual index of Green’s hand; when read carefully, they become jarring and curious, slowly leading the viewer to meaning amid the initial incoherence. Green’s text is poetic and complex - language and thought translated densely from memory in ink, sharpie, and colored pencil on robust panels of wood. Figures and their embellishments are drawn without a hierarchy in terms of space occupied on the surface; they are at times elaborate and at other times profoundly simple. The iconic figures’ facial expressions (Jesus, Abraham Lincoln, Tina Turner, video game characters, etc.) are generally flat with proportions stretching and distorting subject to Green’s intention.

Ultimately, these drawings compel the viewer to internalize and decipher Green’s ongoing, non-linear narrative. His drawings call to mind Deb Sokolow’s humorous, text-driven work, but are less diagrammatic and concerned with the viewer. In an interview with Bad at Sports’ Richard Holland, Sokolow elaborates on her process:

I’ve been reading Thomas Pynchon and Joseph Heller lately and thinking about how in their narratives, certain characters and organizations and locations are continuously mentioned in at least the full first half of the book (in Pynchon’s case, it’s hundreds of pages) without there being a full understanding or context given to these elements until much later in the story. And by that later point, everything seems to fall into place and with a feeling of epic-ness. It’s like that television drama everyone you know has watched, and they tell you snippets about it but you don’t really understand what it is they’re talking about, but by the time you finally watch it, everything about it feels familiar but also epic. (Bad At Sports)

Much like Sokolow, Green engages in making work that begins with the rigorous practice of archiving information culled from his surroundings and interests, which then develops into intriguing, fictitious digressions. Dates and times, tv schedules, athletes, historical figures, and various pop culture references flow through networks of association - “KURT RUSSEL GRAHAM RUSSEL RUSSEL CROWE RUSSEL HITCHCOCK AIR SUPPLY ALL OUT OF LOVE…” Although the listing within his work sometimes gives the impression of being intuitive streams of consciousness, most of it proves to be very structured and complex within Green’s system. Rather than expression or even communication, the priority seems to be the collection of information or organization of ideas; the physical encoding of incorporeal information as marks on a surface is a method for making it tangible, possessable, and manageable.

Daniel Green, Pure Russia, 2011, Mixed media on wood, 9 x 23 x 3.5 inches

Pure Russia (detail)

From the perspective that Green invents, there’s an endless number of time sequences that haven’t been considered before. A grid of days and times (as in Pure Russia) imagines time passing in increments of one day and several minutes, then returns to the beginning of the series, stepping forward one hour, and proceeding again just as before. It could be cryptic if you choose to imagine these times having a relationship to one another, or it could instead be an original rhythm whose tempo spans days, so that it can only be understood conceptually as an ordered structure mapped through time - the significance of the pattern superseding that of specific moments.

By blurring the distinction between the articulation of ideas through text and the development of mark-making, Green’s highly original objects become unexpectedly minimal and material, yet simultaneously personal and expressive.

Daniel Green’s work will be included in Mapping Fictions, an upcoming group exhibition opening July 9th at The Good Luck Gallery in LA, curated by Disparate Minds writers Andreana Donahue and Tim Ortiz. Green has exhibited previously in Days of Our Lives at Creativity Explored (2015), Create, a traveling exhibition curated by Lawrence Rinder and Matthew Higgs that originated at University of California Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (2013), Exhibition #4 at The Museum of Everything in London (2011), This Will Never Work at Southern Exposure in San Francisco, and Faces at Jack Fischer Gallery in San Francisco.

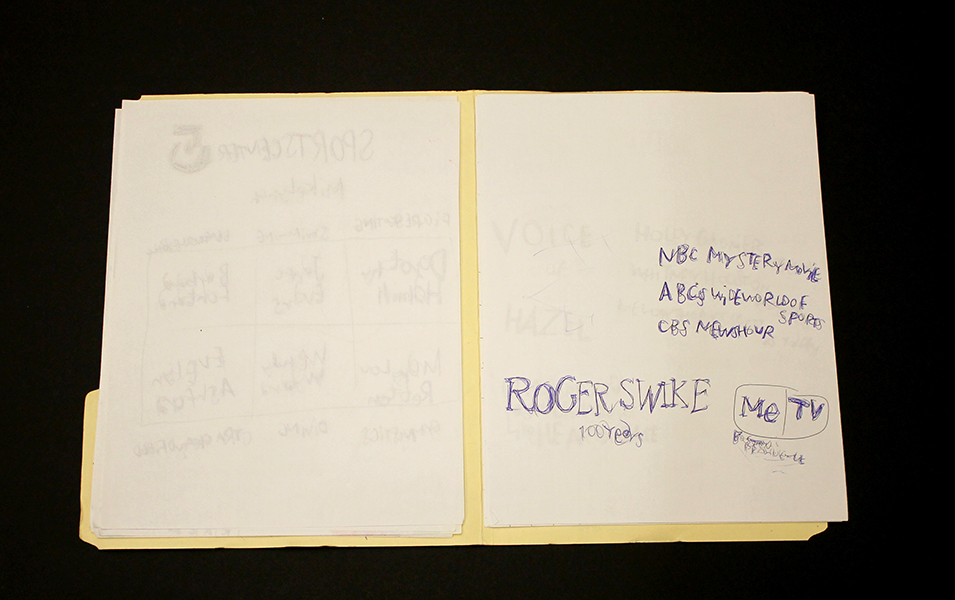

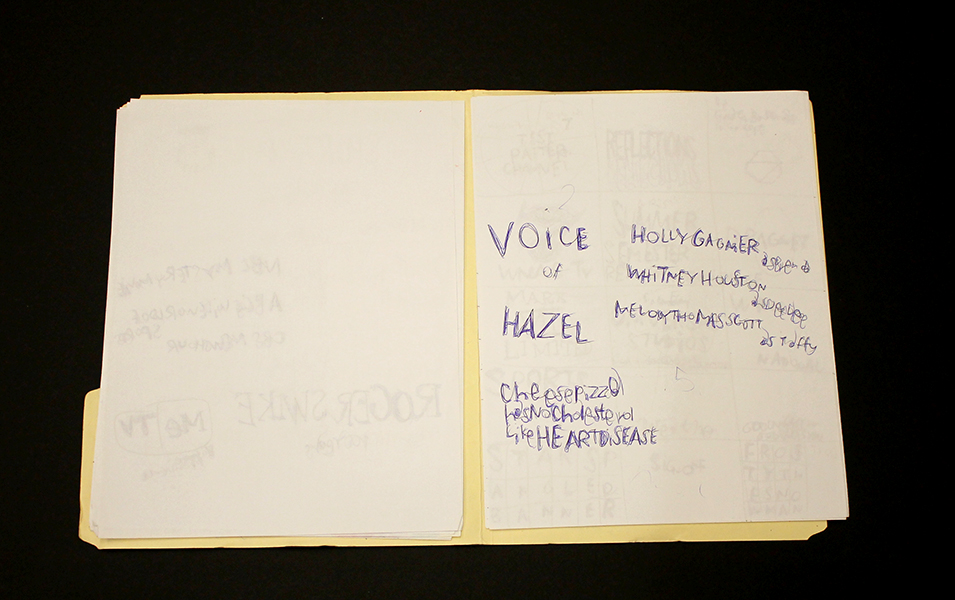

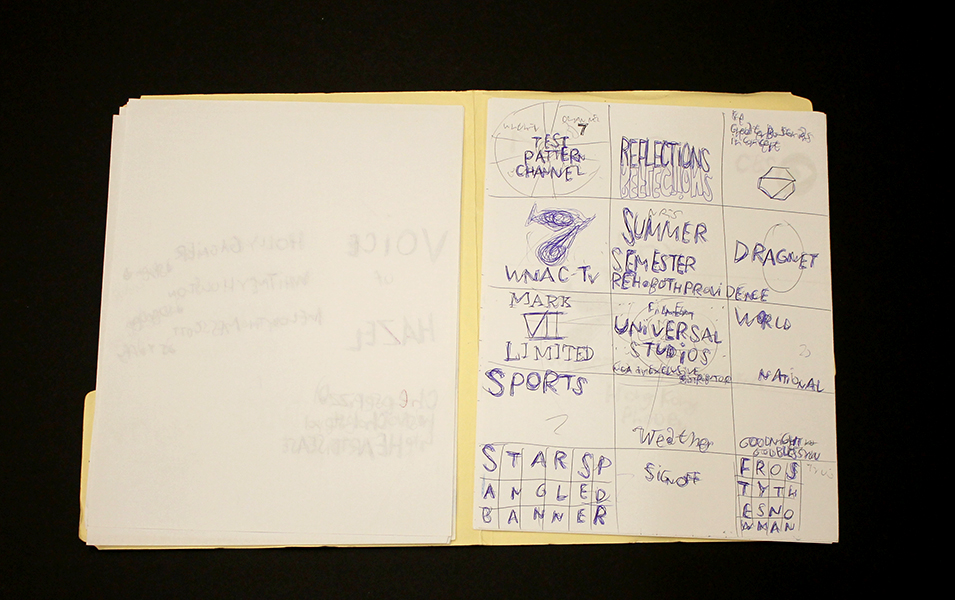

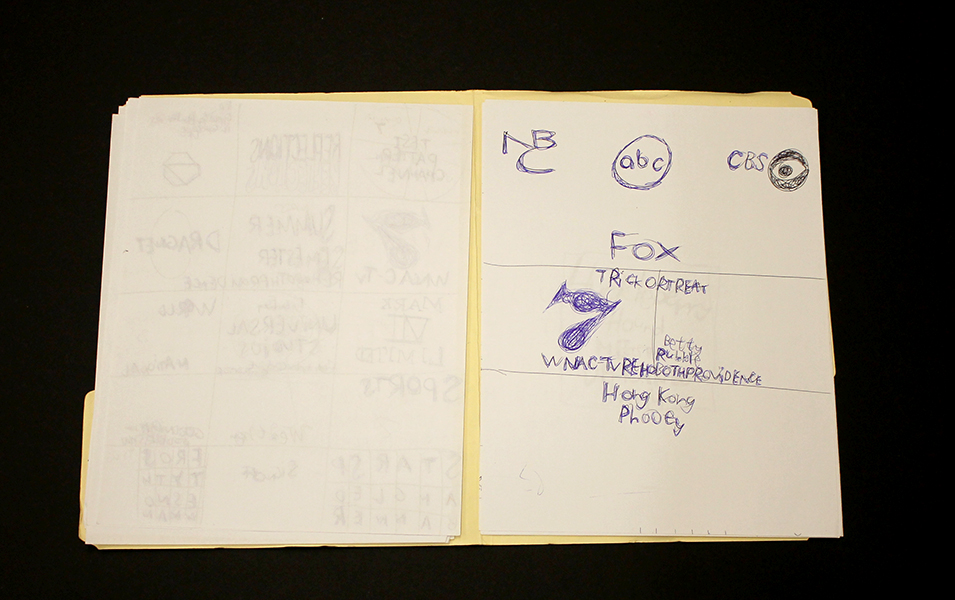

Mapping Fictions: Roger Swike

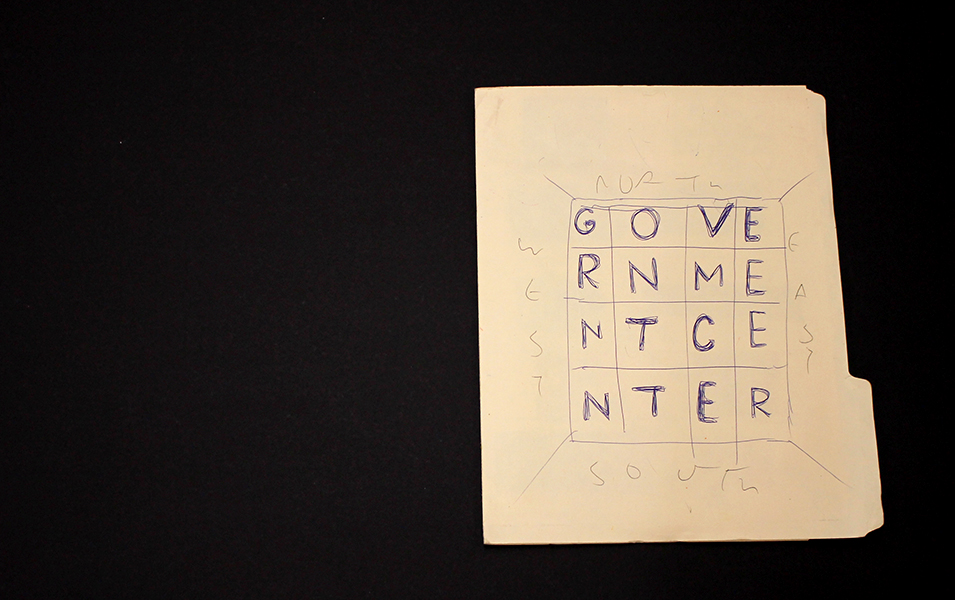

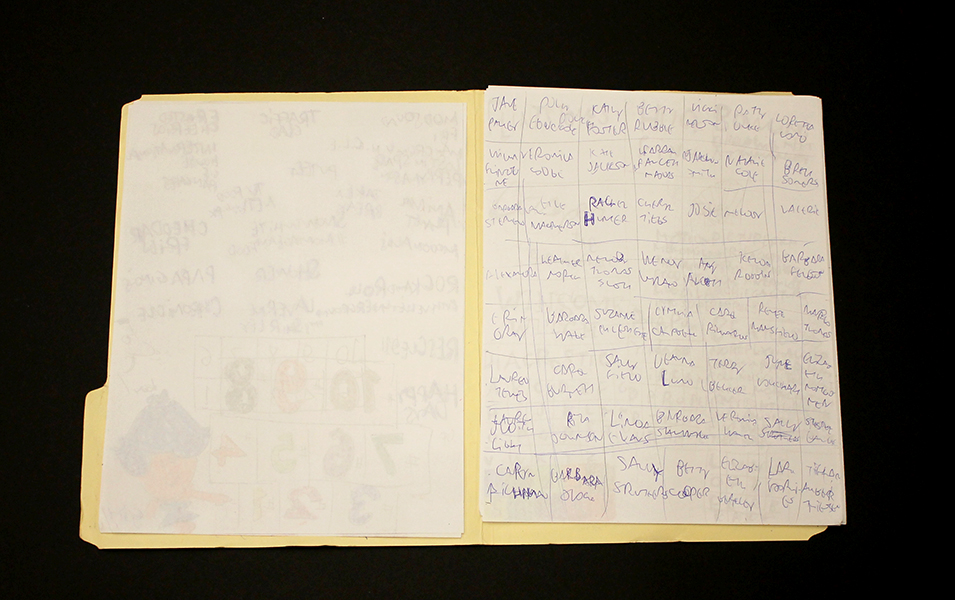

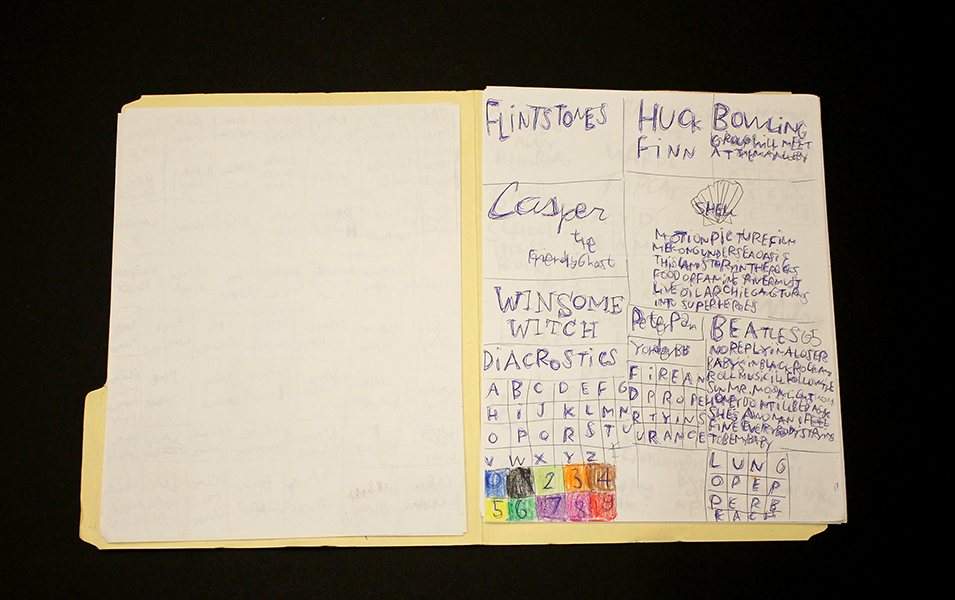

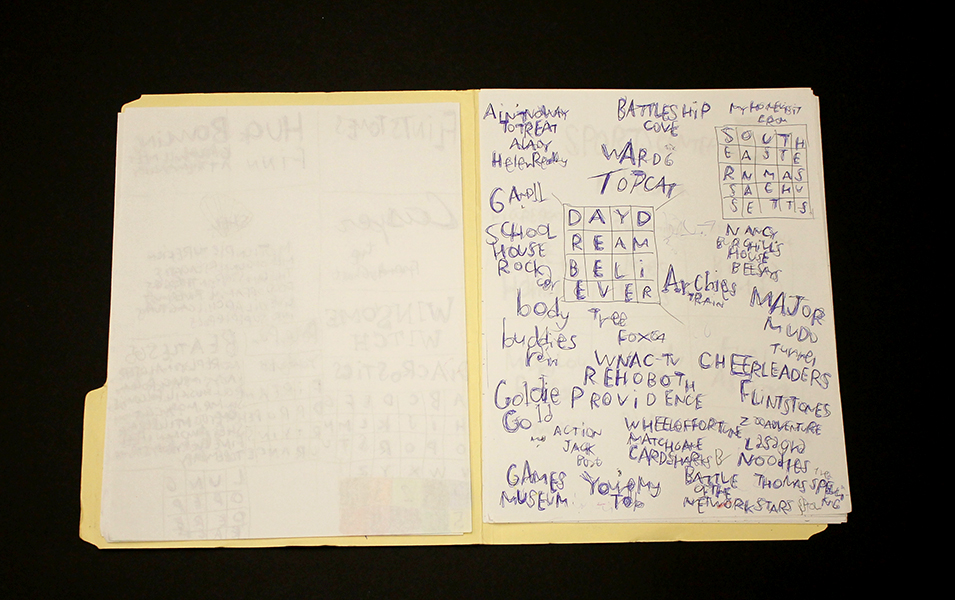

Untitled, ballpoint pen on paper, 12 x 9 inches

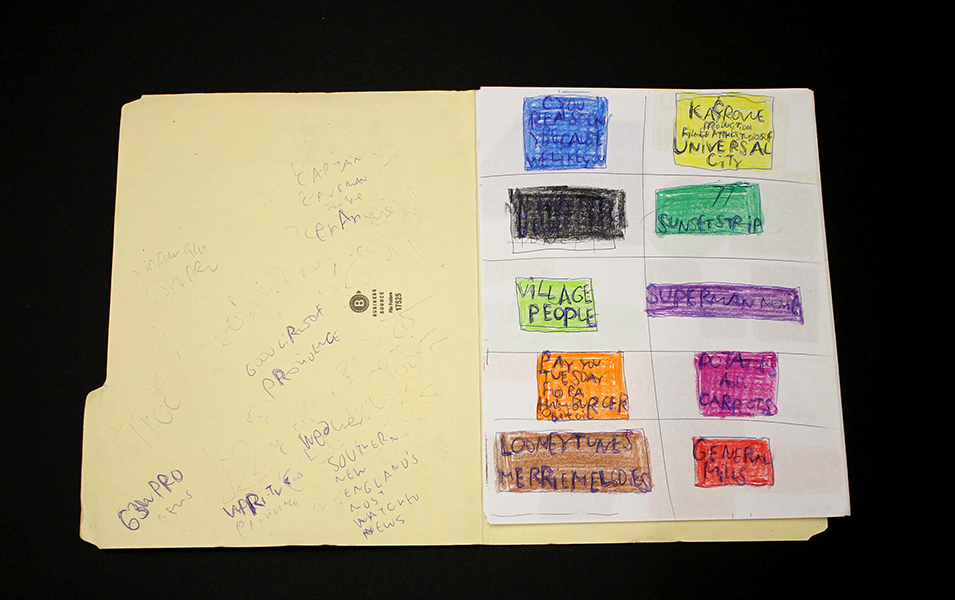

Untitled, ballpoint pen and crayon on paper, 12 x 9 inches

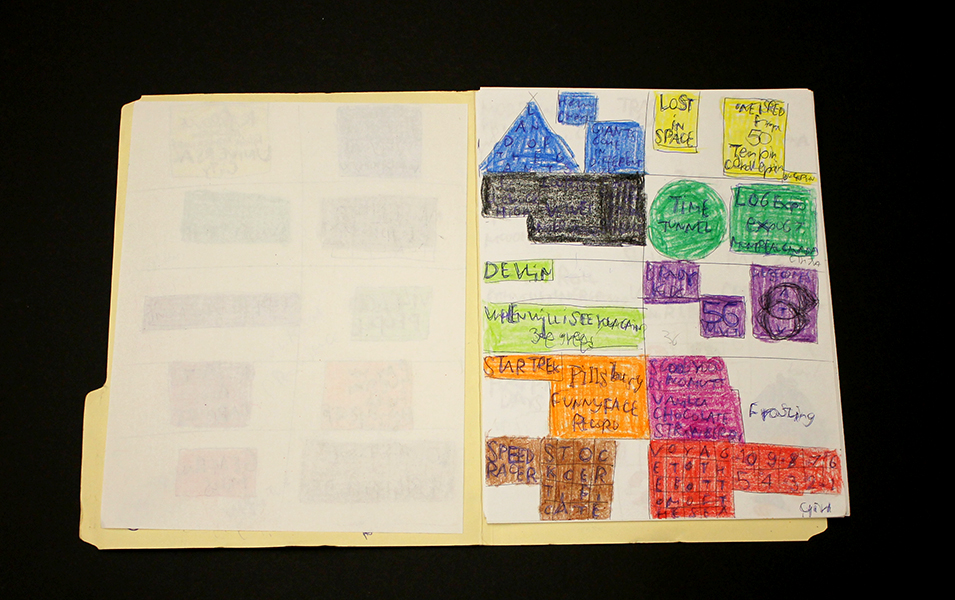

Untitled, ballpoint pen and crayon on paper, circa 2013 12 x 9 inches

Roger Swike's ten crayons

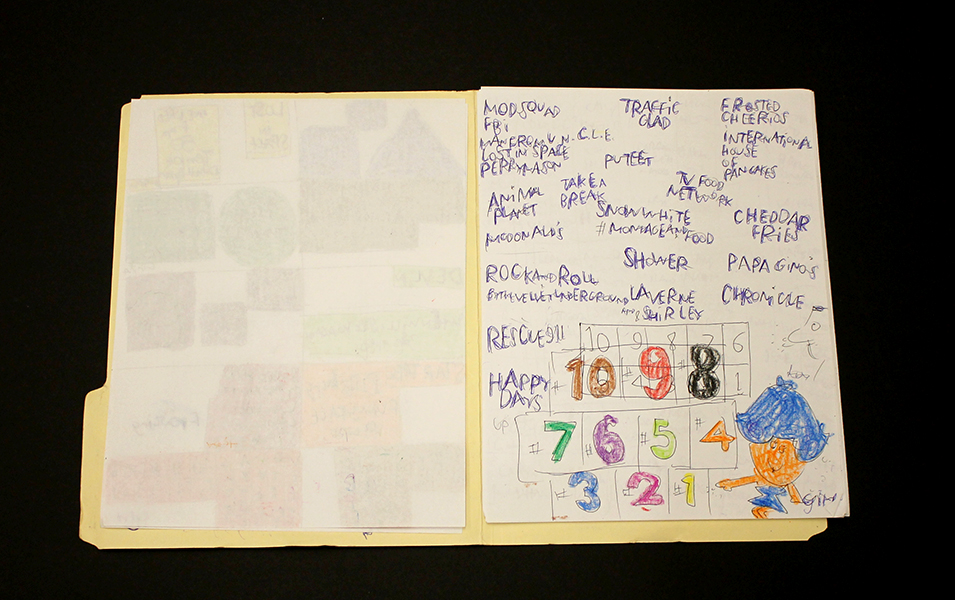

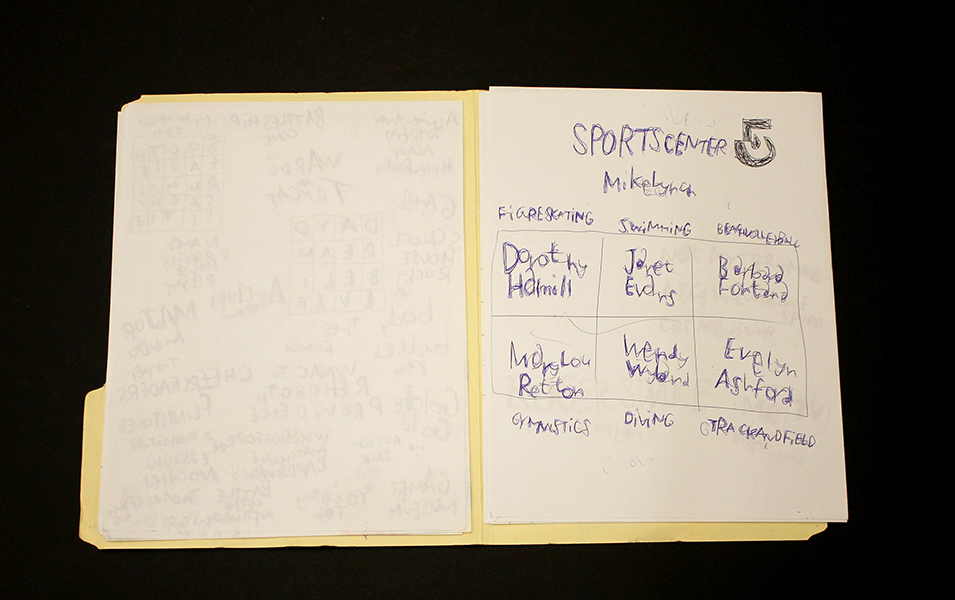

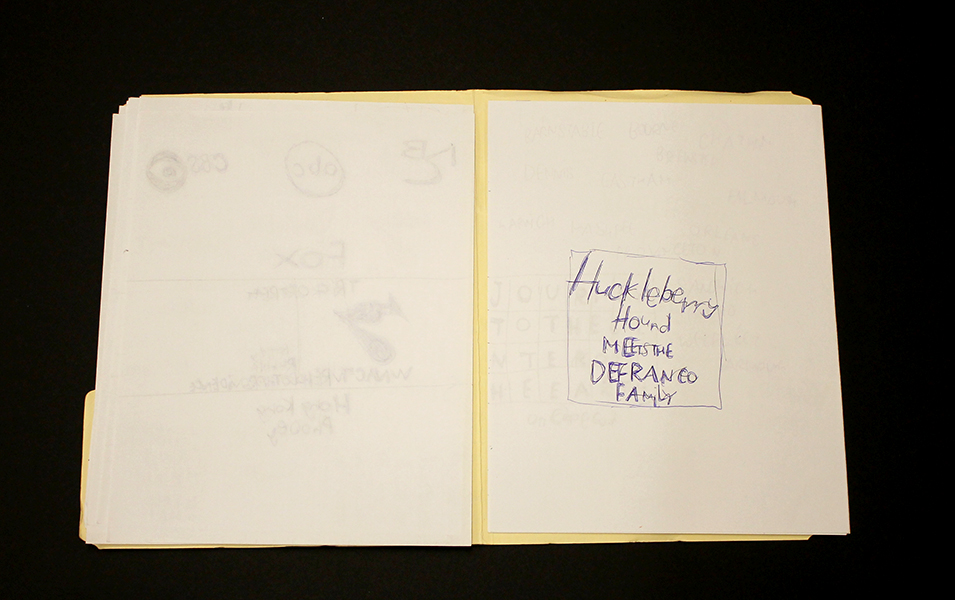

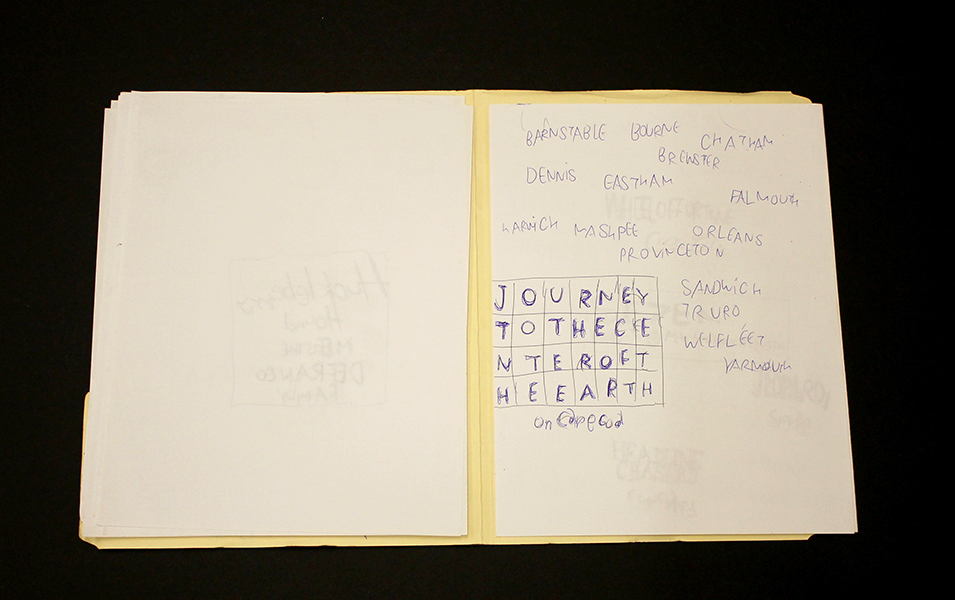

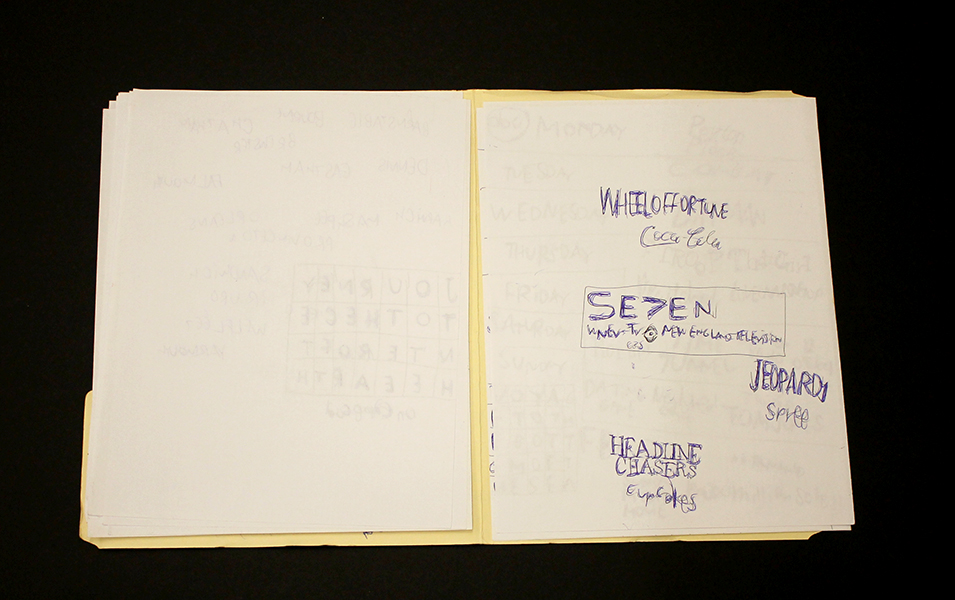

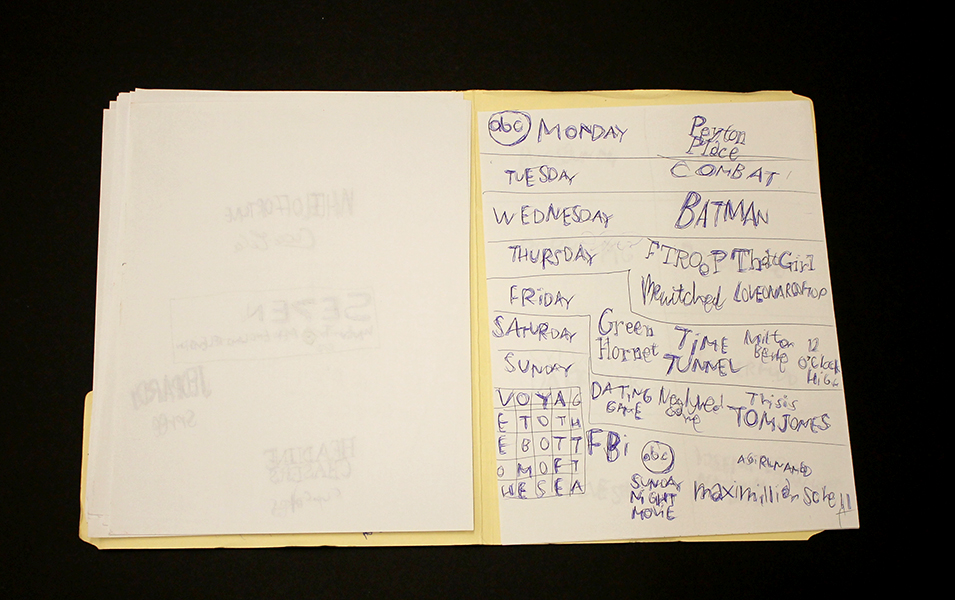

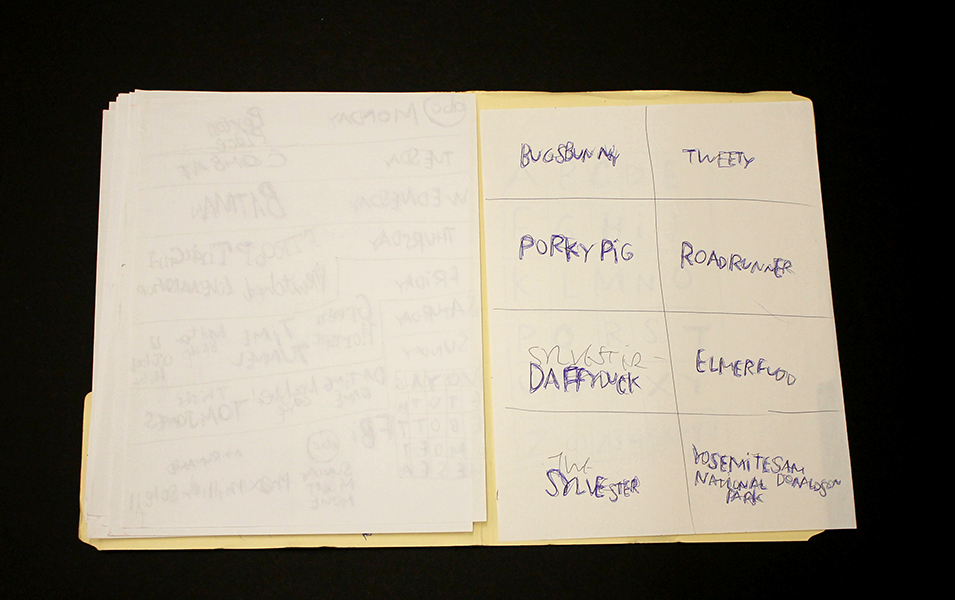

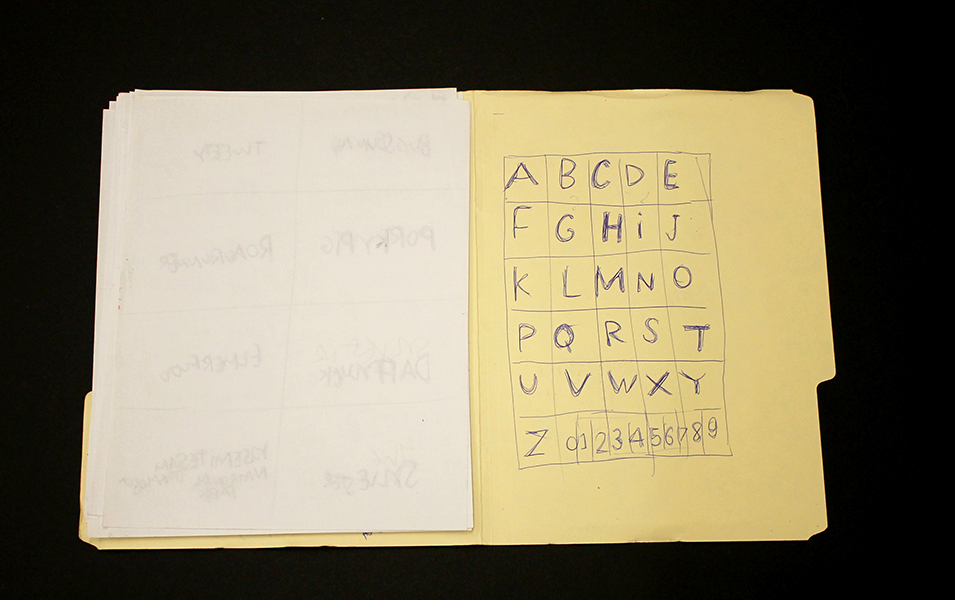

Roger Swike is an exceptionally prolific artist who works rapidly on many pieces simultaneously; much like Melvin Way, his drawing process channels an immediate and intuitive stream of information, yet is also executed with deliberation and great intention. Swike will often revisit drawings created at different times and deliberately organize them into various color-coded folders; the resulting works are an assertive, endearing proposition about what an art object can be. Within content that initially appears chaotic or arbitrary, familiar text referring to pop culture and the exterior world is pervasive. Black and blue ballpoint pens and ten crayons are utilized as though each tool has a symbolic role. Some ideas are organized neatly into grids, others are written in less regimented clusters or lists, primarily in multiple layers of ballpoint pen. Over time, curious relationships and subtle patterns emerge, such as references to the number 7 or numbers listed on their own counting down from ten (but when listed alongside the alphabet they ascend from 0 to 9).

Because Swike’s work is disciplined and systematic, the viewer is tempted to decipher the rigid system that defines it, but the true nature of the work seems to reside in the plasticity of its rules. A grid listing Loony Toons characters deviates from the pattern to include "YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK SAM DONALDSON", numbers are written in black ballpoint pen without an overlapping of blue pen, words or phrases are redacted, yet the sequence and grid are still drawn using the ten selected colors…often it feels as though Swike isn't creating the system, but instead exploring it as a poet does language, both fluent and curious. Each time Swike's lexicon is revisited, it presents an opportunity to rethink its mysterious nature - possibly an archive, message, map, poem, or something else entirely.

Roger Swike’s work will be included in Mapping Fictions, a group exhibition curated by Disparate Minds writers Tim Ortiz and Andreana Donahue at the Good Luck Gallery in LA, July 9 - August 27. Swike (born in Boston, 1962) has shown previously at the Berenberg Gallery in Boston, Fuller Craft Museum, the Outsider Art Fair, Margaret Bodell Gallery, and Phoenix Gallery in New York. He has also been awarded a MENCAP award in London, England.

We first encountered Roger Swike’s work many years ago, as studio co-managers and facilitators in a progressive art studio in Nevada; we began visiting other studios while traveling (before the inception of Disparate Minds). Swike has maintained a studio practice at Gateway in Brookline, Massachusetts (the oldest progressive art studio in the US) since 1995. Despite this, his extensive body of work remains relatively unknown outside of the Boston area, possibly because the art world hasn’t quite been ready for work as contemporary and singular coming from a living, so-called outsider artist.

Knicoma Frederick

Knicoma Frederick, Untitled (Candle Army Eyes) from the Series 80 Bit, 2006, Acrylic on canvas, 24” x 18”

Knicoma Frederick, Glory News Article from the Series Information 1600, 2012, marker and pen on paper, 8 ½” x 11”

Knicoma Frederick, Untitled (Elaborately Painted Pedicure) from the Series 80 Bit, 2008, colored pencil on paper, 8 ½” x 11”

Knicoma Frederick, from the series Die Evil 82, 2013

Knicoma Frederick, Unitled (Couple Painting/Interior) from the Series 80 Bit, 2010, Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 24 inches

“The painting is not on a surface, but on a plane which is imagined. It moves in a mind. It is not there physically at all. It is an illusion, a piece of magic, so what you see is not what you see … I think that the idea of the pleasure of the eye is not merely limited, it isn’t even possible. Everything means something. Anything in love or in art, any mark you make has meaning and the only question is ‘what kind of meaning?” - Philip Guston

Prolific visionary Knicoma “Intent” Frederick has lived the intensely dedicated life of an artist for whom painting is more than painting - it’s a way to access something deeper than merely tangible or social ends. Frederick’s work engages the practice of image design and creation with a mystical or prophetic intent, relying on and striving to access and utilize the magic inherent in the process of painting.

Sometimes remarkably akin to the work of William Scott, Frederick’s work possesses an abundance of idealism, realized as utopian visions of the future - proclamations from Glory News, superhero first responders defeating armies of demons, or a “love and justice” rocket ship flying overhead. Where Scott has a steadfast tone of praise and celebration, however, Frederick’s narrative works also include darker, stranger, sometimes ominous themes that afford them a sense of gravity, conflict, and romance.

Knicoma Frederick, Untitled (Couple Painting/Beach Scene) from the Series 80 Bit, 2010, Acrylic on canvas, 36" x 24"

Works such as Untitled (Couple Painting/Beach Scene) live in a space characterized by a more cryptic sort of mysticism, in which painting becomes not only the method that Frederick employs, but also becomes incorporated into the content of the image - overtly, when paintings are included in the image, and less explicitly when “painting” as an archetype is present in the work via the presence of painting tropes (such as a dramatic seascape or elements of traditional still life). These tendencies also present themselves in the work of Los Angeles based painter John Seal.

In response to our inquiry about Frederick and the concept of paintings of paintings Seal remarked:

"The magic, really, is in the disconnect/misconnect. It is in the way the subject and its material delivery interface/intermesh with the viewer's life experiences--it is the surprise of finding anything in common, the surprise of seeing one's self, altered and new, reflected in the painting which in turn becomes new in the viewer's eyes. The magic is in this dual rebirth of viewer (subject) and painting (object). The magic is the painting's ability to make this dual rebirth visible. Painting paintings of paintings is, to me, a way to lead people into the mechanics of image, and to invite the viewer to examine their own relationship to looking: if a picture can be captured by a picture via the means (language) of painting, what can it do to the rest of the world?"

Knicoma Frederick harnesses these mechanics to not only compel the viewer to reflect on the capacity of painting, but to also assert the presence of his message in the world he envisions. The "dual rebirth" that painting facilitates is, for Frederick, a pathway into this realm that his work manifests, and painting is explicitly the magic by which this manifestation takes place.

In the course of discussing his WPIZ series of artist books, and a fictional video game called ArtFighter (which exists within WPIZ) Frederick articulates his manipulation of this mystical function of painting:

"People have heard of games like ‘Street Fighter’ and ‘Mortal Combat’ and ‘Tekken’ for PlayStation and XBox and all of those different types of game systems…But ‘Art Fighter…is fighting with artwork. You’re taking artwork and you’re fighting the situation with it. You’re taking a picture that represents what you want to have happen, done by the storyline in each book. You’re taking a picture, and you’re destroying the negative with it…I have an obligation to make the WPIZ so that the books are used for overcoming the evil that’s in the people’s way." (source)

Shortly before the establishment of the Creative Vision Factory (where Frederick maintains his studio practice), Director Michael Kalmbach encountered Frederick attempting to get permission at a drop-in mental health center to use the copy machine (unsuccessfully), presumably for the distribution of a handwritten series of newspapers (in the neighborhood of six hundred pages). Kalmbach cites this event as instrumental in the development of CVF (informing its goals, design, and function), not only due to the magnitude of this endeavor, demonstrating the need for and potential value of a studio of this kind, but also that the content of these newspapers provided important insight about both Frederick's personal experience and the mental health system in general.

Frederick’s works are conceptualized as series of books for which each work represents a specific page. Over the four years that he has been with CVF, he has published more than 25 artist books, each comprised of 125 - 150 works; prior to the publishing a book, the works can not be sold individually. Frederick has an extremely productive creative practice; Kalmbach estimates that he creates roughly 1000 works per year.

Knicoma Frederick is originally from Brooklyn, New York, but is currently based in Wilmington, Delaware. Recent exhibitions include All Different Colors and Outsiderism at Fleisher/Ollman in Philadelphia and previously at numerous venues in Wilmington, Delaware. He has work in the permanent collection of the Delaware Art Museum and is the recipient of an Emerging Individual Artist Fellowship from the Delaware Division of the Arts.

Courttney Cooper

Cincinnati Map, 2010, ballpoint pen on collaged paper, 64" x 88"

Untitled, 2015, ballpoint pen on collaged paper, 52" x 80"

Cincinnati Map, 2009, ballpoint pen on collaged paper, 51" x 85"

Cincinnati Map, 2009 (detail)

Cincinnati Map, 2009 (detail)

images courtesy Western Exhibitions and Visionaries + Voices

Cooper’s oeuvre is a ongoing narrative featuring Cincinnati, imparted with adoration and idealism. Drawings that are tenaciously committed to archiving the city’s developing reality in bic ballpoint pen, Cooper documents the destruction of old buildings and construction of new ones, while modifying details to reflect the time of year (often after they've been hung in an exhibition space). But they are also richly populated with celebratory, idealistic imagery - flags flying on rooftops, hot air balloons traversing the sky above the river, “Do not be afraid, be a precious friend! Zmile, you’re in Zinzinnati Ohio USA 2011”.

Cooper’s works are often characterized as maps, which isn’t an entirely accurate categorization. Visionaries + Voices’ Krista Gregory points out:

I've come to learn that Courttney has been drawing "aerial views" of Cincinnati since he was a small child, first using an etch-a-sketch. His mark-making certainly reflects having this type of information/tool...I see the work that Courttney creates more in the vein of landscape, or townscape; as they are romantic in their visceral love for this place...I think that this work being categorized as ‘maps’ is misleading and couches them in something that is more related to Courttney's disability rather than to what it is that he is actually expressing and creating. They are not accurate. They are not drawn completely from memory. I've witnessed people hold on to wanting to think these things because it makes the work accessible or novel in some way. I sort of think that it is a reductive way to see them

The desire to see Cooper’s works as maps may be the consequence of trying to categorize autistic thinking - relegating autistic artists as spectacles of savant-ism. Courttney Cooper, however, is not comparable to Stephen Wiltshire, for example; his drawings are not an accurate configuration of streets as a road map indicates, nor are they a repetitious anonymous depiction of a city in an illustrative way. They're indeed informed by an intimate experience with his city - an astounding wealth of information accumulating across increasingly massive surfaces (created by gluing together scrap paper that Cooper gathers while working at Kroger). But this isn't the subject of the work, it's only the formal foundation that serves as a vehicle for Cooper’s voice. Cooper’s drawings are a complex and authentic network of specific places and structures; his streets are composed of details from memory or observation, cataloging expressions of particular perceptions in particular moments. The relationship of these moments to each other in space is approximated, as in memory - all of which culminates in a dizzying realm of overlapping information that becomes a living record, adorned generously with nostalgic, commemorative expressions of community and identity.

Zinzinnati Ohio USA: The Maps of Courttney Cooper curated by Matt Arient, is a selection of Cooper's drawings from 2005 - 2015, currently on view at Intuit through May 29th. Cooper is represented by Western Exhibitions in Chicago, where he has an upcoming solo exhibition November 12 - December 31, 2016. Cooper has maintained a studio practice at Visionaries + Voices in Cincinnati since 2004; he has exhibited extensively in the greater Cincinnati area and has work in the Cincinnati Art Museum collection. Selected exhibitions include the Wynn Newhouse Exhibition at Palitz Gallery, Syracuse University (as a 2015 Wynn Newhouse Award recipient), Cincinnati Everyday at the Cincinnati Art Museum, Maps + Legends: The Art of Robert Bolubasz and Courttney Cooper at Visonaries + Voices, Studio Visions at the Kentucky Museum of Art, Cincinnati USA: Before Meets After at PAC Gallery, and Indirect Observation at Western Exhibitions.

Insights from Ari Ne'eman

Recently Disparate Minds had the opportunity to have an encouraging and insightful conversation with Ari Ne’eman about progressive art studios, the incredible work they do, their future, and their relationship to the disability rights movement. Ari is a hero of the movement, particularly as a champion of autism rights and autistic self advocacy; he’s the co-founder and current president of the Autism Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) and was appointed by President Barack Obama to chair the National Council on Disability’s Policy & Program Evaluation Committee in 2009 (Ne’eman is the first autistic person to ever serve on the council).

As we’ve traveled around the country speaking with directors of progressive art studios, a common concern, almost everywhere, has been how these programs can continue as regulations regarding medicaid services change - that phasing out the practice of providing medicaid funded services in a “congregated” or “sheltered” setting could threaten their existence. Strangely, progressive art studios seem to find themselves at odds with the broader disability rights movement as a direct result of this. As we’ve researched to understand this issue, we’ve found that representatives of the disability rights movement generally just aren't aware that progressive art studios exist or familiar with their impact or importance. Other than a general awareness of the VSA (a network of providers affiliated with the Kennedy Center offering some art related services to children with disabilities), Ari also had no prior knowledge of progressive art studios, had never heard of Creative Growth or Judith Scott, and didn’t know that at the center of our culture, the art world, there’s an incredible shift occurring in the way that developmental disability is currently understood.

During our visit with Creativity Explored director Amy Taub, responding to a question about developing practices to accommodate future regulations (such as an integrated or community based model that works) said “this is what works”. Studios like Creativity Explored have, for decades, provided day programs supporting artists to have independence, agency, and place in our culture to a degree beyond the the most idealistic dreams of any other form of service provider. Championing the voices and ideas of people with disabilities in national and international forums, in public works and large-scale commercial endeavors. And yet, Taub also conceded poignantly that progressive art studios are an incredibly small fraction of medicaid providers for day or employment services.

Through exhibitions, artists like Marlon Mullen achieve a profound connection to a broader community.

Furthermore, it’s not only studios that aren’t well known or understood among disability service providers, but art itself. The achievements of artists like Judith scott, Dan Miller, Courttney Cooper, Marlon Mullen, Julian Martin, and Helen Rae feel monumental; it’s easy to forget how small and obscure the art world really is to the majority of the population. The reality is that most people wouldn't know who Larry Gagosian or Jeff Koons are, nevermind Matthew Higgs or Andrew Edlin, even as their influence touches so many aspects of our culture. The social impact of contemporary art isn’t married to public knowledge of its agents; the average IKEA customer has likely never heard the name Donald Judd. The impact that progressive art studios have made and can make, is enormous and unprecedented in history for people with disabilities, even as the most successful examples of artists from progressive art studios remain mostly unknown.

We believe that even though progressive art studios are currently a relatively small fraction of services provided, the work they pursue is essential. We decided to reach out to Ari Ne’eman and discuss this specifically in response to his own comments on the relationship of the disability rights movement to social and cultural change. In this video Ari responds to a question about the lack of social and cultural victories made by the disability rights movement, conceding that the movement has focused on making valuable legal and policy advancements by “soft selling” the cultural and social impact that’s aspired for. He states, “We haven’t excelled at turning out large numbers of people, we haven’t excelled at winning social and cultural victories” and that the movement is “not well-geared towards winning hearts and minds”; as a result of this and the movement being insular in nature, Ne’eman says, “We don't see the broader cultural conversations about disabilities that we see in the context of other identities.”

Winning hearts and minds while creating broad cultural conversation is exactly what progressive art studios are doing, better than any other model for support. We conveyed to Ari the feeling expressed to us by many progressive art studios that “congregating” or “facility-based” programs are unfairly regarded to be necessarily less progressive than integrated community-based supports, arguing that although progressive art studios aren’t integrated spaces in a traditional sense, they affect integration and inclusion in their respective communities and cultures through exhibitions, which ultimately provide a categorically more authentic presence for the voices and ideas of artists with disabilities than simply being physically present does.

We also argue that even though integration is possible and is being pursued by several studios, it may not be without a cost to the studio’s effective functioning, as well as their social impact. Currently, we argued, these studios are emerging in the contemporary art conversation as a new model for artists’ careers and development, and it’s important that this movement belongs to artists with disabilities and their respective studios. Even ignoring the practical disadvantages of transitioning to a system in which artists with disabilities rent studio space to work alongside neurotypical artists (with facilitators visiting to work with them as job coaches), this is a change that would undermine these artists’ ability to make a case for their place in history not only as artists who are successful despite disability and receiving services, but as artists for whom being disabled and receiving services is an integral part of their identity, their lives, and their creative practice. These artists’ disability and dispositions as recipients of services should be understood as a legitimate cause to congregate as artists, because it should be understood as a legitimate way of being.

The studio at the Center For Creative Works in Philadelphia PA is a rich creative community

Ari’s response to this was encouraging and compelling. He expressed that integrating progressive art studios wouldn't have to mean eliminating the studio itself, or even depriving it of its identity as a space for artists with disabilities, it just needs to also be open to artists without disabilities who aren’t paid supports. Ari explained that this isn’t just about the social impact of integration, but also how integration affects the delivery of services. This is something easy to forget, as our focus has been on the handful of studios who are the most progressive and successful in the world, where delivery of services isn’t a concern. Looking more broadly, that there are a great many programs who provide art, even in an open studio setting that aren’t as effective as they should be - who are not as organized, progressive, or person-directed as they should be. It’s undeniable that the quality of services provided by staff would, as a whole, be better if staff were also working with neurotypical artists. In this sense, it’s impossible to deny that if all service providers providing day programs were required to be open and appealing to neurotypical artists using their space alongside artists with disabilities, they would be forced to use more progressive practices. It’s significant that this idea only makes any sense for art studio programs - they’re the only kind of day program that would be appealing to neurotypical artists if they become open to them.

Ari explained that there has been a focus on integrating and improving residential and employment services more than day services, and he committed to us that he’ll keep progressive art studios in mind as attention shifts to day services. In response to our description of the progressive art studio model, Ne’eman emphasized a few key points that will be important going forward:

- Focus on benefit to the individual served

Although the social and cultural impact of progressive art studios and their artists is important, it should never be prioritized over benefit to the individual. This means facilitating and supporting career management in a way that always prioritizes the artist’s wants and needs above all other concerns, including social impact, or benefit to the program or its staff. This means not exhibiting or selling an artist's work if they don't want it exhibited or sold, even if that exhibition would provide valuable exposure for the program as a whole. This also means being very careful about collaborative projects, which are often regarded as a good way to connect with the community, but which could also present a high risk for exploitation.

- Severability of services

The relationship of the program to the artist needs to be such that the artist is able to continue their life and career even if they chose to use another provider. This is a concern that stems from problems identified in residential services in which service providers are also landlords, so ending or changing services means moving out of their home.

For progressive art studios this has important implications in two dynamics of the model. One is ownership of the artists’ works - both physical inventory and as intellectual property. Agreements have to be very clear from the start about how this is managed in the event that an artist chooses to stop being a part of the studio or move to a different studio. The other dynamic is the marriage of habilitation/care services and art facilitation/career management services. Having artists work with artists in the studio is essential, so the dual role of artist staff as facilitators and direct care or habilitation staff is an ideal arrangement. The principle of severability of services would seem to also require that the artist should be able to continue to use the studio even if they prefer to use a different provider for rehabilitation services, or if they chose to discontinue their habilitation or care services. The latter is arguably more essential, and certainly more feasible, as it would simply require that the artist pay for their use of the studio by some other means, as neurotypical artists using the studio would in an integrated arrangement.

Eliminating scheduling of regular hours

One of the essential aspects of a progressive art studio described by Lawrence Rinder in discussion of the Create exhibition was that the artists work in the studio during “hours which reflect the common work hours, five days a week 9-5”. However, artists shouldn’t be in agreement with the studio to attend at certain times as they would attend work or school, but may set goals to invest a particular amount of time and devise plans that use a schedule to meet that goal. In practice, this seems to boil down to a mere matter of language, but it’s based on an important principle; artists in progressive art studios aren’t paid an hourly rate, so they can’t obliged to attend particular hours. Attendance policies or schedules that have a compulsory feeling are left over from less progressive models - an artist's use of the studio should be understood as self-motivated.

The most encouraging insight from this conversation was that the future of progressive art studios may be not only to sustain as regulations change, but to broaden scope and expand as a new definition of what day programming is. If studios are understood not as part of an outmoded form of service, but as the examples of the ideal model for a still relevant and important one, then day programs in general can be redefined, no longer as places where people with disabilities are accommodated, but as spaces for creativity, in which a truly neurologically diverse group of creative people congregate to utilize tools, materials, and work space with guidance and support as needed - spaces that are for expression, entrepreneurship, and all manner of making, whose existence is a statement about the essential relationship of diversity to productivity as paragons of the most extreme expression of those principles.

Marvin Asino

From the Disparate Minds collection: “For all of my friends and one basketball player” is a zine containing 21 poems interpreted from the text works of Marvin Viloria Ariza Asino. It’s sensibility can be described using Marvin’s own words “rhythm; kind, beautiful, friendly.” Asino writes in a matter-of-fact manner (siding in a space where humor and simple, profound truths meet), so the force of its beauty comes entirely by surprise with a wonderful sense of mystery.

This anthology was given in the course of a conversation with one of Marvin’s many friends, Robert Grey, at Full Life, in Portland Oregon last year. An updated overview of Full Life, a very different kind of program, will be posted soon.

Progressive Practices: Materials, Archives, and Inventory

“I am glad that I had the guts to make these things, and that people like them, because I want them to live for a long time after I am gone.” - Patrick Hackleman

A remarkable aspect of the progressive art studio history is their independent emergence across the world. Creative Growth in Oakland, California is widely regarded to be the first; they were among the first to be established (Gateway Arts in Brookline, MA was founded shortly before) and they were, by far, the first to break into the art market and support artists that are recognized nationally and internationally. However, the relationship of this first program to subsequent programs elsewhere doesn't strictly follow the typical narrative of a pioneering idea. Their legacy is significant; Franz and Elias Katz went on to establish Creativity Explored and NIAD, and many programs have looked to the bay area as they developed (utilizing the example of Creative Growth as a proof of what's possible with this model). However, versions comparable to the progressive art studio are widespread and usually come into being without any knowledge of Creative Growth or any other studio. It has been and continues to be a naturally occurring phenomenon.

Art-making is an intuitive and fantastically effective solution to many of the issues that various service providers for adults with developmental disabilities strive to resolve. As those of us who work within the field understand, the endeavor to provide the least restrictive environment isn’t a merely passive endeavor, It requires a proactive, thoughtful, and ambitious effort to provide not just a safe space, but also independence, validation, and opportunities to make valued contributions in the community. In a setting based on these aspirations, art-making is a perfect answer, and in some form it tends to be introduced at some point, but in most cases with woefully insufficient ambition or perspective.

Once art is introduced in settings comparable to day programs, a door opens and an important opportunity emerges. From that point on, the success of the program is dependent on how much the staff believe in the potential of the works created to be great, meaningful, and valuable - and how they express that belief. The degree of belief spans a vast spectrum, at one end the artist’s potential is overlooked entirely as they’re encouraged to waste time by following step-by-step instructions to create mediocre craft objects, and at the other end their potential is hindered only by the limitations that the art itself has to be great - a limit that has not yet been discovered by anyone ever. How a progressive art studio demonstrates respect for their artists and belief in their potential is first expressed in tangible terms - how the work is handled and presented (in not only exhibitions, but at all times). The standard of these practices sets the tone for every aspect of the studio’s functioning, permeating the culture of the organization and influencing how the artists perceive their own work and potential.

Because progressive art studios don’t necessarily emerge with the intention of becoming fine art organizations, and often exist within larger organizations for which fine art has not been a part of their history or culture, they tend to reside within a system that isn’t prepared to understand the process of maintaining an art practice. As a result, many basic concepts such as the nuanced quality of materials or the concept that a great piece can be ruined very easily, aren’t broadly understood. Advocating for respecting the work and believing in its potential must be a constant effort, on every level, from the working culture within the studio, to the relationship between the studio and both its parent organization and the community; every choice has to adhere to clear principles with great conviction.

The Canvas' Jeff Larabee working with a selection of archival markers and surfaces

High Quality Materials

The first expression of belief in and respect for our artists’ endeavors is the investment we make in the materials provided. High quality art materials are expensive and great art can be made using very inexpensive materials; Henry Darger and Joseph Yoakum created amazing bodies of work in this manner. However, their work has yellowed and faded over time, with restoration efforts already being utilized to preserve their original integrity. The principle that a studio should follow is to use the highest quality archival and lightfast materials feasible for each artist; this must be a highly individualized facilitation process. New, very prolific artists, or artists who haven’t yet matured in their practice may work with student grade materials, but it’s not unreasonable to provide a very expensive sheet of handmade paper to someone who routinely spends months dedicated to completing a single drawing.

A program should strive to develop a budget capable of maintaining a baseline for quality of materials that, at a minimum, accounts for archival integrity while also allowing room for larger investments in artists who demonstrate promise. As often as possible, these investments and the precious nature of materials should be communicated to the artists. Learning to be attentive to the distinctions in quality and craftsmanship of tools and materials is an important aspect of being a visual artist; developing reverence for a beautiful surface or rich pigments can be an important step in an artist's development.

Great Photo Documentation and an Archival System

For a progressive art studio to create a clear and complete archive of works is an ongoing difficult and time consuming task; even medium or small sized programs easily produce hundreds of individual works each month. No other kind of art organization has such a labor-intensive professional archiving process as the progressive art studio; art schools produce a lot of work without storing or documenting it and galleries, museums, and private collections preserve and document large quantities of works, but they aren't created in house. Therefore, developing a great system to achieve this inevitably requires a bit of thought and innovation. Much like great materials, an archival system can be a huge investment (including proper lighting and camera equipment), but the benefits are equally huge.

The best and most thorough studio archive project we’ve encountered is NIAD’s inventory, which is available to view online in the form of a Tumblr blog - a great resource for what an inventory should ultimately look like. At first glance, it gives you an impression of the program overall, listing works by all artists, with the most recent work at the top. What makes it really powerful, though, is its searchability. You can search a specific artist's name to access their complete body of work, as well as search by medium or year.

There are many ways to achieve a similar system offline. The key is that each work have a distinct identity - a unique accession number that’s included in the filename of the digital image and physically written inconspicuously on the back of the work. These numbers can then be used to store Information about the work, including artist name, title, medium, size, framed or unframed, and whether it’s currently part of the inventory or sold previously in a simple searchable document (database or spreadsheet) separate from the images. This can be great resource for the program to track its own progress, to be aware of and critical about its trends.

An archive such as this makes the difference between being perceived and dismissed as a space for recreation or therapy, and being recognized and revered as a powerful and productive cultural institution. It’s also an extremely beneficial resource for gallerists, collectors, curators, and the press, providing convenient access to an impressive collection of incredible bodies of work.

As important as these pragmatic benefits are, though, is the statement and attitude implicit in developing an impressive archive is more important; the work is either treated as if it’s worth documenting, or as though it is not.

A Clean, Ordered Storage Space and Clean, Careful Handling Practices

Many years ago I worked with a young woman who was caught up in a network of behavior modification obsessed service providers carefully executing “proven” methods to move arbitrary behavioral metrics incrementally. Regretfully, I was never able to fully support her to escape this pseudo scientific culture she was immersed in, but I was able to have her attend our studio for a few days a week, where she was provided with beautiful sheets of pristine drawing paper, on which she made fantastic drawings that were subsequently stored away carefully. During this period of time I visited her home, a state owned “intensive care facility.” Standing in her living room, I was struck by what the the physical nature of the space asserted about the relationships existing within. There were small thrift store artworks hung weirdly high on the wall out of reach, thick glass brick windows, and a tv bolted to a quaint, wooden piece of furniture that was also bolted to the floor with a simple, but sturdy iron armature holding a sheet of 1.5” thick plexiglass in front of the screen, to protect it.

The contrast between the sensibility of this environment and the practice of giving her that valuable, delicate sheet of drawing paper, not only without protecting it from her, but with the presumption that when she was finished, it would be greatly more delicate and valuable than before, could not be more stark (and for home staff accompanying her to the studio, this notion was downright counterintuitive). This example is extreme, but defines a stigma that proves to be a significant barrier to any progressive art studio, especially those that exist as a part of a larger service provider. Day hab programs tend to be spaces defined by a preoccupation with safety, filled with reinforced or disposable versions of ordinary objects. Assembly workshop programs avoid jobs that entail the creation of delicate products or handling of delicate parts. In a setting that fashions itself to be a productive environment, the stereotype that those with disabilities are clumsy and careless is insidiously destructive. Progressive art studios’ designs and intentions aren’t just divergent from traditional programs for people with disabilities, but are actually opposed to and incompatible them; as much as they resemble day programs in form, they are, in almost every dynamic, the exact opposite.

The inventory at Grace Studio in Hardwick, Vermont. In addition to providing access to art to people with disabilities in their community, Grace owns the estate of the late Gayleen Aiken, who previously worked there. Grace received a grant specifically to provide their staff with professional training in handling and maintaining their collection.

A well-maintained and professionally handled inventory of works makes an important statement against this stigma. Progressive art studios need to learn how to handle, package, and store work with the utmost care, not only for obvious practical purposes, but for the sake of the principles that these practices stand for. The understanding that people with developmental disabilities can also create precious art objects worth treating with the highest standards of care is essential to the vision and message.

Like a great archival system, a robust, dependable inventory opens doors for progressive art studios and their artists. A well cared for body of work is an infinitely more compelling proposition to a gallerist than a handful of works carelessly piled onto shelves, stuffed into flat files, or hung arbitrarily on the studio walls. One of the most prevalent, troubling, and confusing phenomenons we discovered during studio visits across the country was artists who were invested in art-making for years having almost no inventory or documentation of work to show for it.

Julian Martin

Untitled (motorbike), pastel on paper, 15" x 11", 2014

Untitled (White on Cream), pastel on paper, 15" x 11 1/4", 2010

Untitled (Orange Shape and Khaki), pastel on paper, 15" x 11 1/4", 2010

Untitled (parrot), pastel on paper, 15" x 11", 2014

Like other progressive art studio artists at the Outsider Art Fair, Julian Martin works from found imagery culled from magazines (often art publications). Whereas Helen Rae pushes found imagery to greater levels of complexity and reality, and Marlon Mullen and Andrew Hostick retell images in their own vocabularies, Martin pares the image down to a series of perfectly resolved moments in which a series of forms (each powerful and resolved in their own right), is described with an abundance of velvety pastel marks applied deliberately and seamlessly with a deft touch. Martin achieves a ubiquitous softness - soft colors, shapes, surfaces, and materials, yet always precise and controlled in application, saturating the surface while maintaining the boundaries of each form with conviction.

Initially, Martin’s work seems aesthetically akin to the work of many young artists currently revisiting concepts of early abstraction with suggestions of the figure, such as Brooklyn-based painters Austin Eddy and Tatiana Berg. However, where these artists revisit and re-imagine the ideas of artists like Picasso and Dubuffet, who were themselves appropriating the aesthetics of outsiders, Martin is the real thing. Not in that he is a “real outsider” (at this point Martin is quite well established professionally, certainly as much an insider as any artist living and working in Melbourne), but rather that his works, in sum, lack any tone of irony or nostalgia; the strength of resolution that each of Julian Martin’s drawings finds is achieved through a minimalist’s sensibility, preoccupied with the absolute rather than a historical context, more comparable to Malevich, Gottlieb, or Mondrian than Cubism or Art Brut.

The proposition underlying Martin's work seems to be that a found image may, inevitably or inherently, possess a more perfect resolution that can be exposed through a measured and thoughtful process of reduction. Unlike Mondrian, the absolute is not found in total abandonment of the original, but in the poetic and specific distillation of the identity and expression of the image.

Martin has attended Arts Project Australia in Melbourne since 1988 and has exhibited extensively at various venues in Melbourne since 1990. He has also shown previously at Fleisher/Ollman (Philadelphia), several Outsider Art Fairs (NYC), Museum of Everything (London), MADMusée (Belgium), Phyllis Kind Gallery (NYC), Jack Fischer Gallery (San Francisco), among others. Martin is represented by Fleisher/Ollman and Arts Project Australia.