We recently had the honor of guest curating an exhibition at The Good Luck Gallery, an important, new space in Los Angeles. Founded and directed by former Artillery publisher Paige Wery, The Good Luck Gallery is the only space in LA dedicated to showing the work of self-taught artists. Wery fosters the burgeoning careers of artists such as Helen Rae and Deveron Richard, who maintain studio practices in progressive art studios, as well as artists like Willard Hill, who fall into the Outsider, Visionary, or Vernacular categories. Mapping Fictions, curated by Andreana Donahue and Tim Ortiz, opened on July 9th and will be on view through August 27th.

Read MoreMapping Fictions: William Scott

Inner Limits to the Future of Hollywood of the Real Science Fiction Movies, acrylic on canvas, 48" x 54", 2013

The Twilight Zone, acrylic on canvas, 36" x 48", 2014

Inner Limits Will Exist in 2017 of a Real People of New Science Fiction, acrylic on paper, 25" x 33"

San Francisco-based artist William Scott is a believer in a better society, a self-described “peacemaker” and “architect”. His works are the celebratory announcement of the wholesome future; they not only imagine an alternate universe reflecting his personal aspirations, but proclaim with joyous conviction his utopian vision of San Francisco, “Praise Frisco”. Scott’s paintings, drawings, and sculptures are executed in an aesthetic consistent with this gospel of idealism and excellence, shining with a pristine vibrance.

William Scott’s paintings of cityscapes and beaming figures surrounded by bold text are well known and widely collected; Mapping Fictions will also include lesser known works that delve into specific plans for Praise Frisco that demonstrate surprising depth and scope, beyond just a notion of that place. In these works, Scott strives to pull the world he sees into reality by imagining its common details. Optimistic plans for ordinary architecture, floor plans of “Disneywood” condos, and development company logos all express directly that this could actually exist with an earnestness reflected in a letter to the Mayor Gavin Newsom, calling for or announcing the news of Praise Frisco.

Scott’s work can be understood in the context of the intent and ideals of Theaster Gates or Bertrand Goldberg, who have employed the traditional agency of art-making to guide communities in inventing better versions of themselves.

Like Goldberg, Scott’s architectural drawings and models recall the spare, utilitarian designs for community housing as envisioned by the Bauhaus, an idealistic solution for social progression. Goldberg “was more than an architect - he was also a philosopher. In his utopian worldview, architecture had the power to create democratic communities by serving people from all levels of society while remaining sensitive to the needs of individuals. Architects were not just capable of bringing about a better future for everyone, they were morally obligated to do so.” (source)

Disneywood in Hunters Point Areas in San Francisco for the Redevelopment Agency, marker and ink on paper, 8.5" x 11" 2006

Hunters Point Hills in 2040s for New Developments, marker and ink on paper, 18" x 24", 2007

Theaster Gates’ creative practice extends beyond his studio as social activism, urban planning, and the ethical redevelopment of distressed properties, which manifests as an immediate, tangible influence that Scott’s work does not. There proves to be commonality, however, in the ambition to activate change and critically engage the public through art. Both Scott and Gates are driven to preserve and resurrect values from the past and a sense of community that has been lost. Gates explains:

The reimagining is a means to an end, and sometimes it is its own end. There are wasted opportunities that are waiting to be beautiful again, and I'm giving them a charge. It's not so much that the buildings on Chicago's South and West sides are vacant, but that they started to lose value for the black community. These buildings had so much soul, but we imagined that, because of the violence and the schools, we should be somewhere else. So these buildings lost their soulfulness. I'm interested in showing there is still so much latent power in these buildings, and by simply making these spaces available again, and open again, great things can happen. (source)

Whether an intentional fiction, genuine aspiration, or prophecy, Scott’s elaborate narrative is a creative vehicle for social commentary, as well as a context for an impassioned and highly personal expression of his commitment to recurring concepts of humanity, spirituality, identity, and community.

William Scott’s work is included in the upcoming exhibition Mapping Fictions, curated by Disparate Minds founders Tim Ortiz and Andreana Donahue, July 9 - August 27 at The Good Luck Gallery in LA. Scott (b. 1964) maintains a studio practice at Creative Growth in Oakland, California. Scott is widely collected and has work in the permanent collections of the MOMA and The Studio Museum in Harlem. He has exhibited previously in solo exhibitions at White Columns and group exhibitions at Park Life Gallery (San Francisco), Gavin Brown’s Enterprise and the Outsider Art Fair (NYC), Hayward Gallery (London), Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (San Francisco), the Armory Show (NYC), Palais de Tokyo (Paris), and NADA (Art Basel, Miami).

Change to Mayor Edwin Lee, Ink on paper, 8.5" x 11", 2003

Mapping Fictions: Daniel Green

Daniel Green, Fifteen People, 2009, Mixed media on wood, 14.25 x 22.5 x 1.75 inches

Daniel Green, Little Mac vs Soda Poponski, 2015, mixed media on wood, 11.5 x 15 inches

Daniel Green, The Sun, 2015, mixed media on wood, 6 x 16.5 x 1 inch

Daniel Green, Business Delivery, 2011, Mixed media on wood, 13 x 29 x 1 inches

Daniel Green's process is slow and intimate; quietly hunched over his works in the bustling studio, he draws and writes at a measured pace. These detailed works are an uninhibited visual index of Green’s hand; when read carefully, they become jarring and curious, slowly leading the viewer to meaning amid the initial incoherence. Green’s text is poetic and complex - language and thought translated densely from memory in ink, sharpie, and colored pencil on robust panels of wood. Figures and their embellishments are drawn without a hierarchy in terms of space occupied on the surface; they are at times elaborate and at other times profoundly simple. The iconic figures’ facial expressions (Jesus, Abraham Lincoln, Tina Turner, video game characters, etc.) are generally flat with proportions stretching and distorting subject to Green’s intention.

Ultimately, these drawings compel the viewer to internalize and decipher Green’s ongoing, non-linear narrative. His drawings call to mind Deb Sokolow’s humorous, text-driven work, but are less diagrammatic and concerned with the viewer. In an interview with Bad at Sports’ Richard Holland, Sokolow elaborates on her process:

I’ve been reading Thomas Pynchon and Joseph Heller lately and thinking about how in their narratives, certain characters and organizations and locations are continuously mentioned in at least the full first half of the book (in Pynchon’s case, it’s hundreds of pages) without there being a full understanding or context given to these elements until much later in the story. And by that later point, everything seems to fall into place and with a feeling of epic-ness. It’s like that television drama everyone you know has watched, and they tell you snippets about it but you don’t really understand what it is they’re talking about, but by the time you finally watch it, everything about it feels familiar but also epic. (Bad At Sports)

Much like Sokolow, Green engages in making work that begins with the rigorous practice of archiving information culled from his surroundings and interests, which then develops into intriguing, fictitious digressions. Dates and times, tv schedules, athletes, historical figures, and various pop culture references flow through networks of association - “KURT RUSSEL GRAHAM RUSSEL RUSSEL CROWE RUSSEL HITCHCOCK AIR SUPPLY ALL OUT OF LOVE…” Although the listing within his work sometimes gives the impression of being intuitive streams of consciousness, most of it proves to be very structured and complex within Green’s system. Rather than expression or even communication, the priority seems to be the collection of information or organization of ideas; the physical encoding of incorporeal information as marks on a surface is a method for making it tangible, possessable, and manageable.

Daniel Green, Pure Russia, 2011, Mixed media on wood, 9 x 23 x 3.5 inches

Pure Russia (detail)

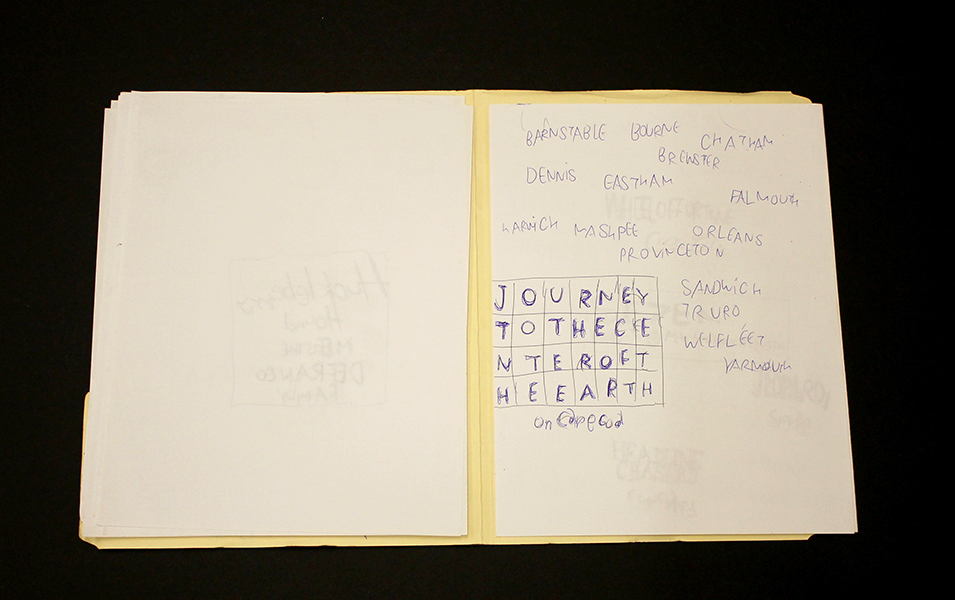

From the perspective that Green invents, there’s an endless number of time sequences that haven’t been considered before. A grid of days and times (as in Pure Russia) imagines time passing in increments of one day and several minutes, then returns to the beginning of the series, stepping forward one hour, and proceeding again just as before. It could be cryptic if you choose to imagine these times having a relationship to one another, or it could instead be an original rhythm whose tempo spans days, so that it can only be understood conceptually as an ordered structure mapped through time - the significance of the pattern superseding that of specific moments.

By blurring the distinction between the articulation of ideas through text and the development of mark-making, Green’s highly original objects become unexpectedly minimal and material, yet simultaneously personal and expressive.

Daniel Green’s work will be included in Mapping Fictions, an upcoming group exhibition opening July 9th at The Good Luck Gallery in LA, curated by Disparate Minds writers Andreana Donahue and Tim Ortiz. Green has exhibited previously in Days of Our Lives at Creativity Explored (2015), Create, a traveling exhibition curated by Lawrence Rinder and Matthew Higgs that originated at University of California Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (2013), Exhibition #4 at The Museum of Everything in London (2011), This Will Never Work at Southern Exposure in San Francisco, and Faces at Jack Fischer Gallery in San Francisco.

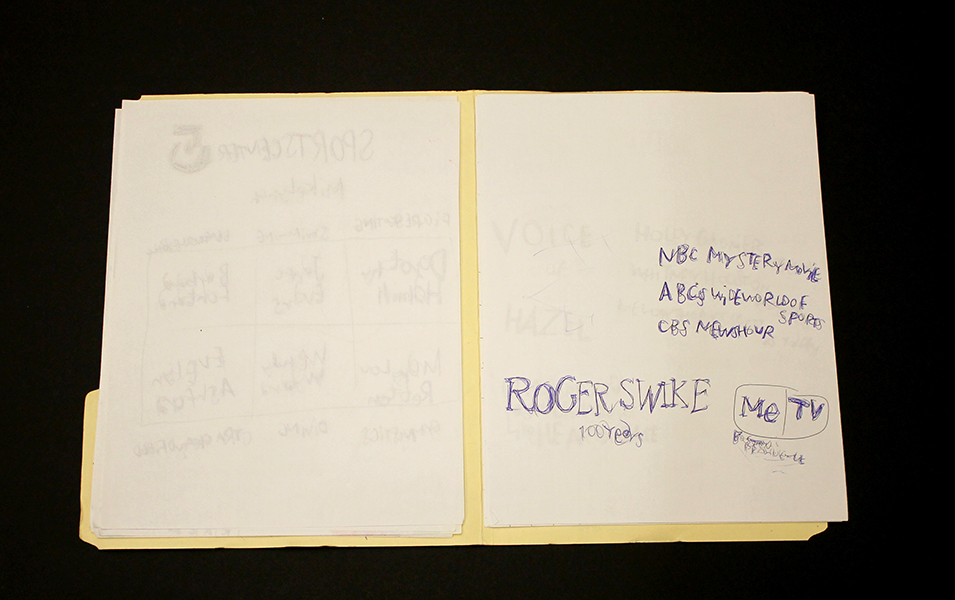

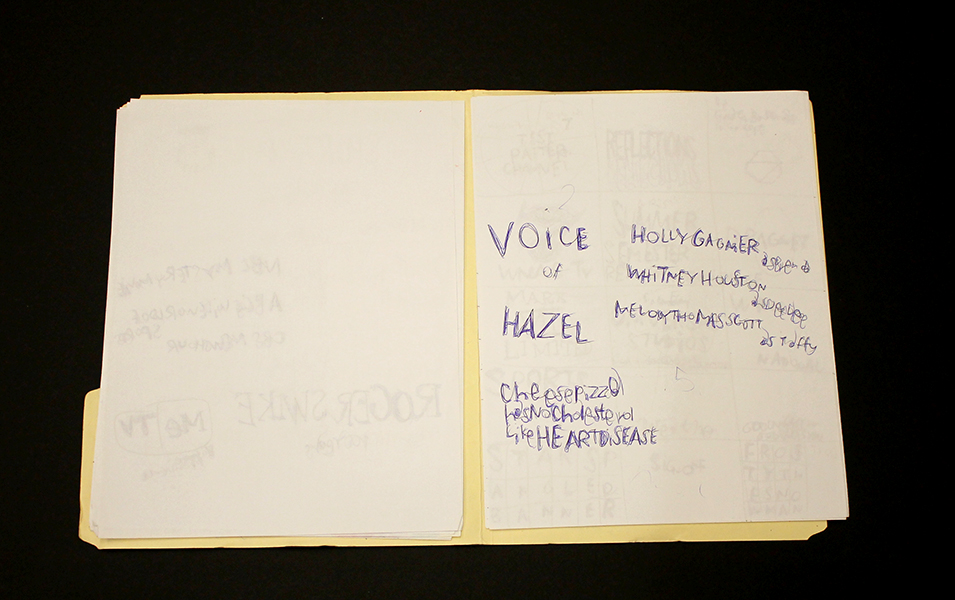

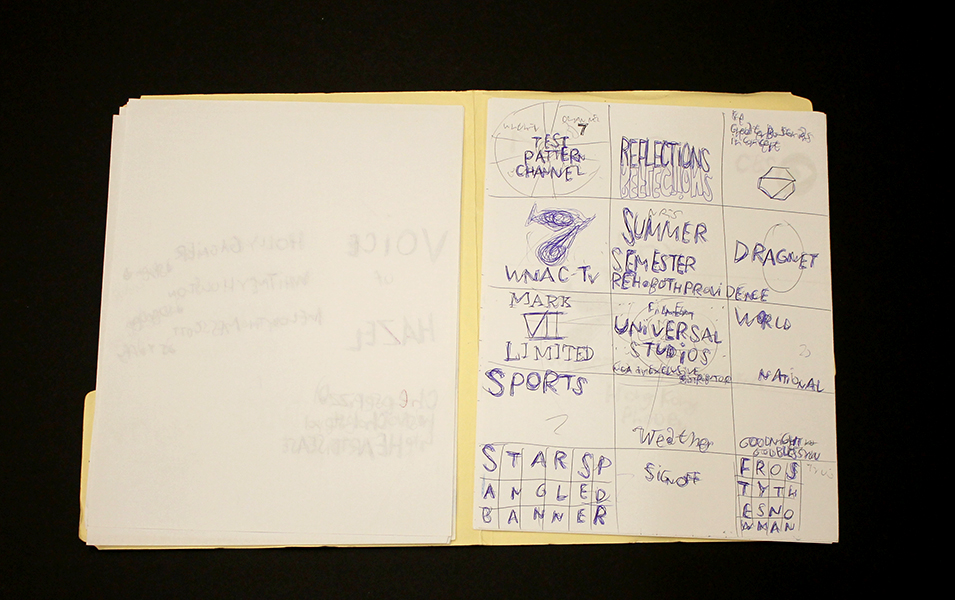

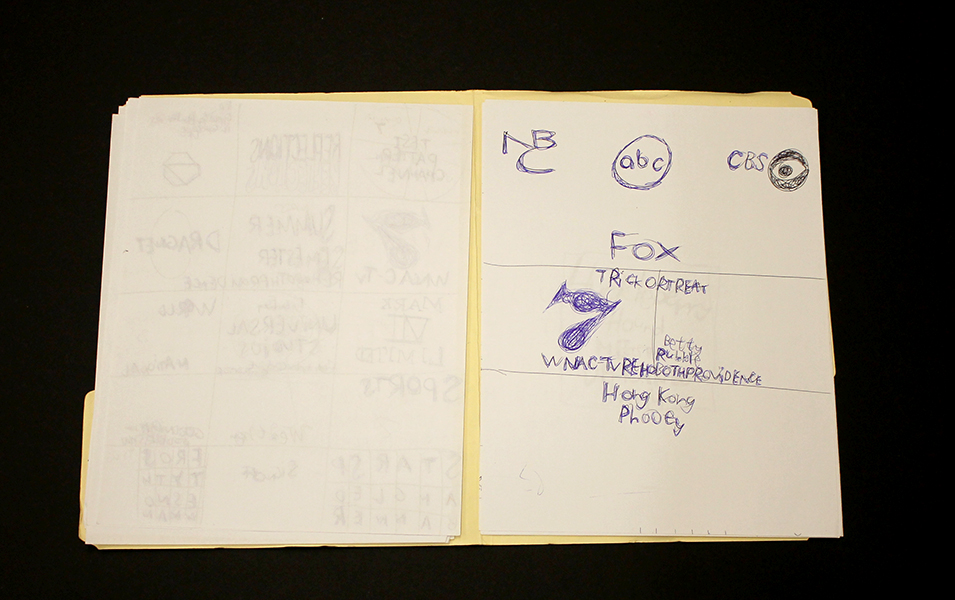

Mapping Fictions: Roger Swike

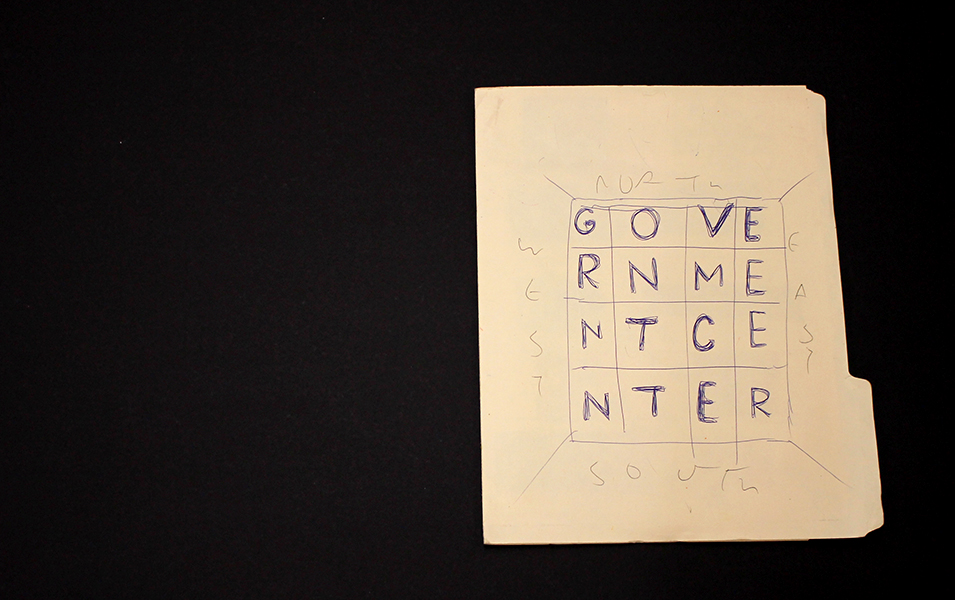

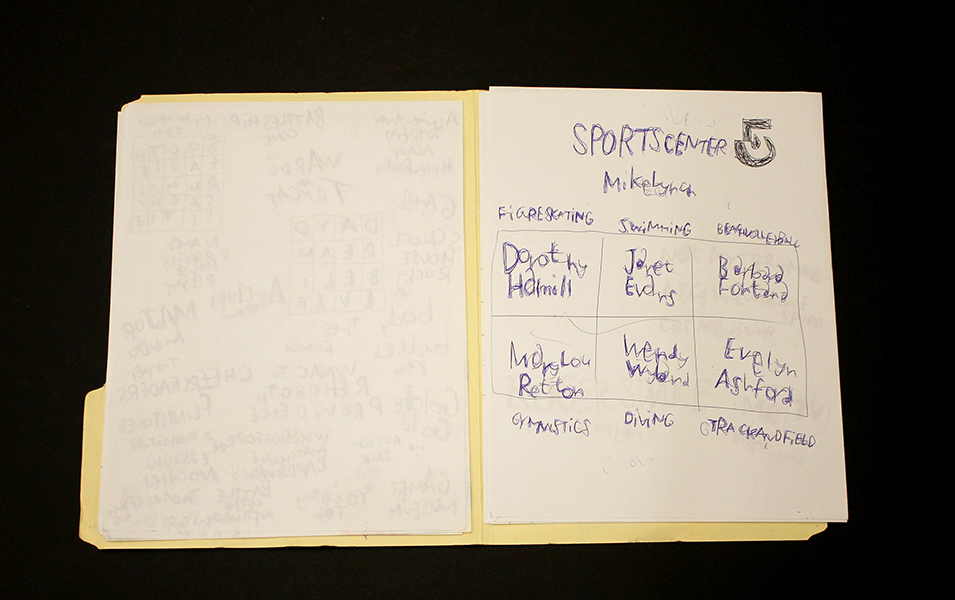

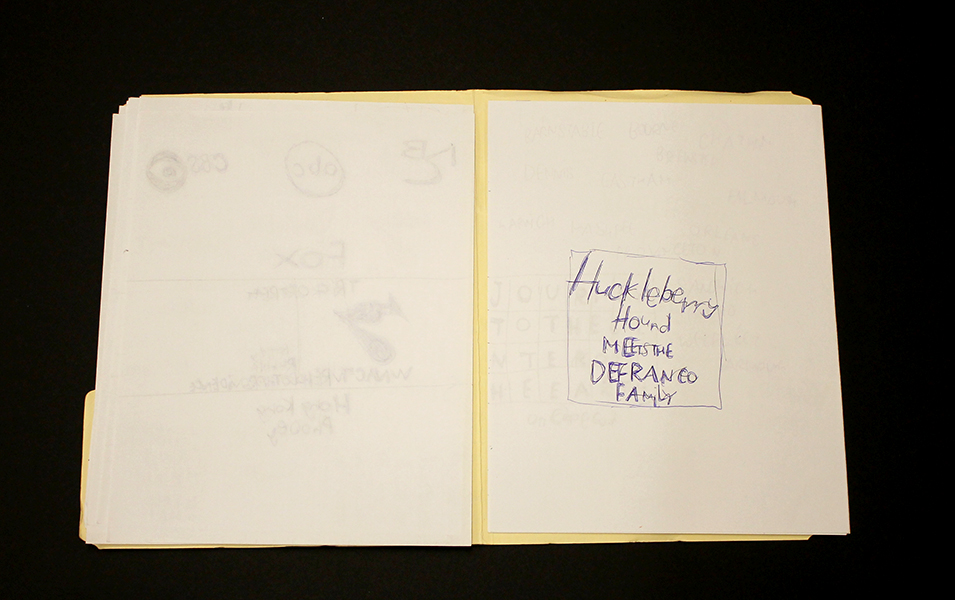

Untitled, ballpoint pen on paper, 12 x 9 inches

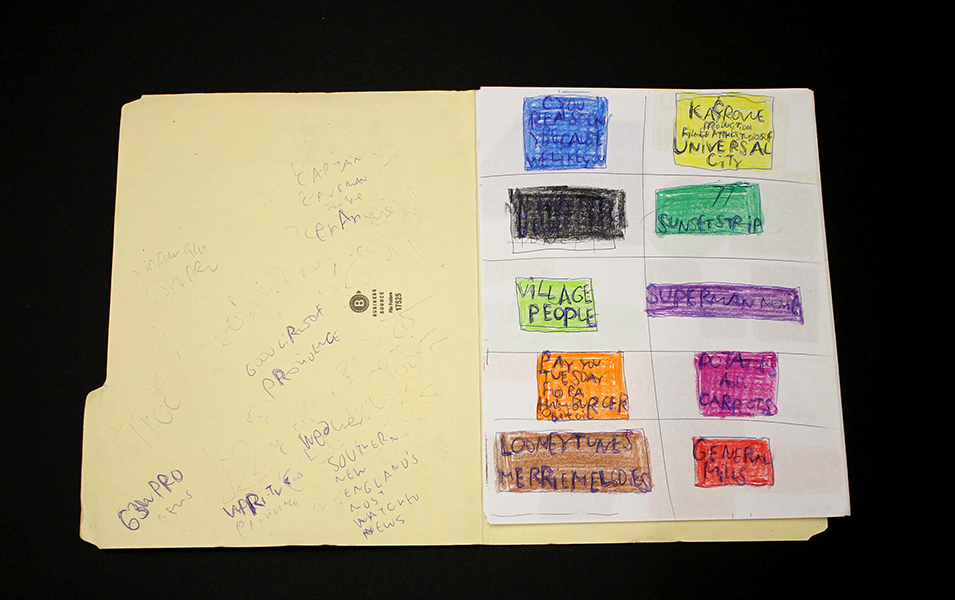

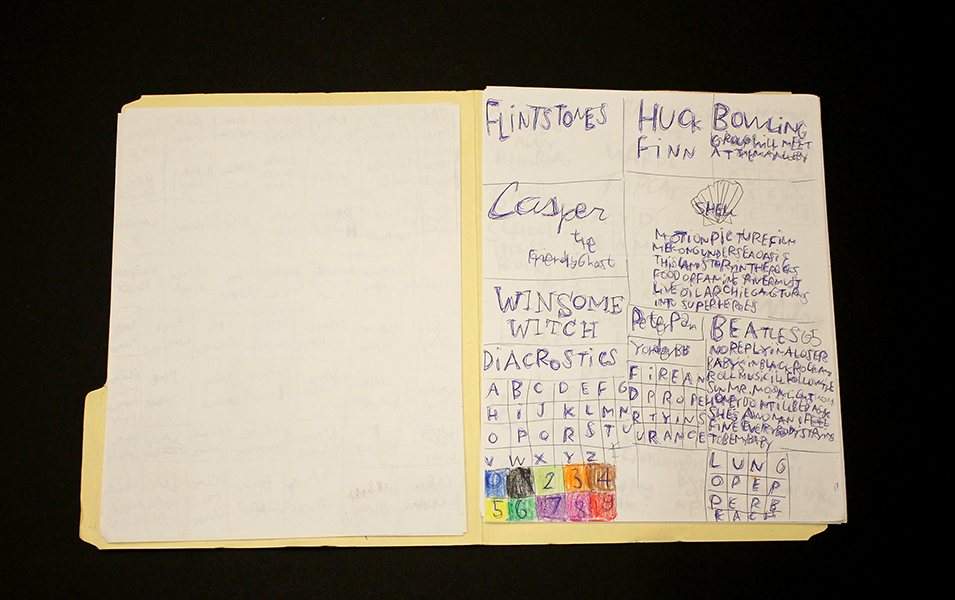

Untitled, ballpoint pen and crayon on paper, 12 x 9 inches

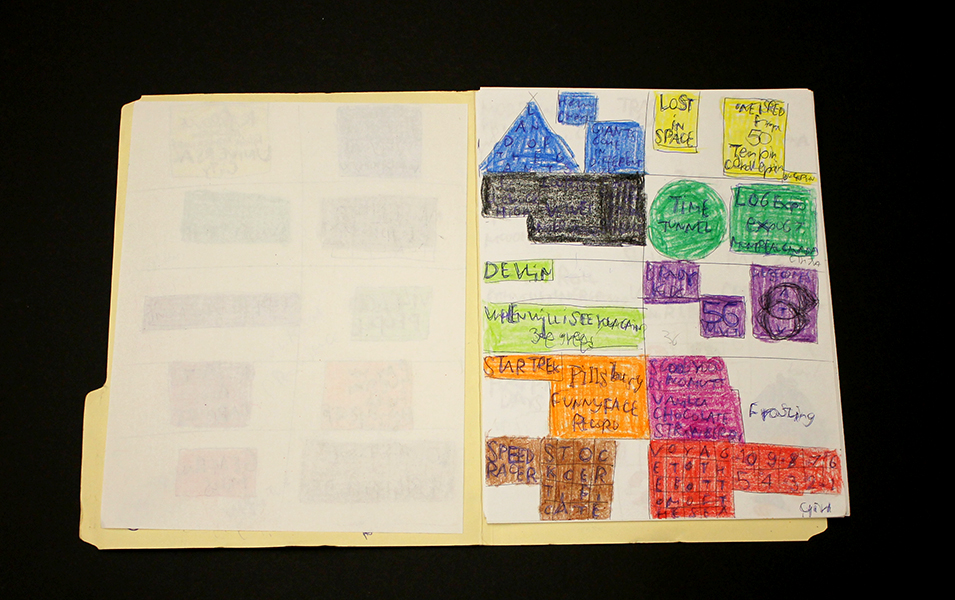

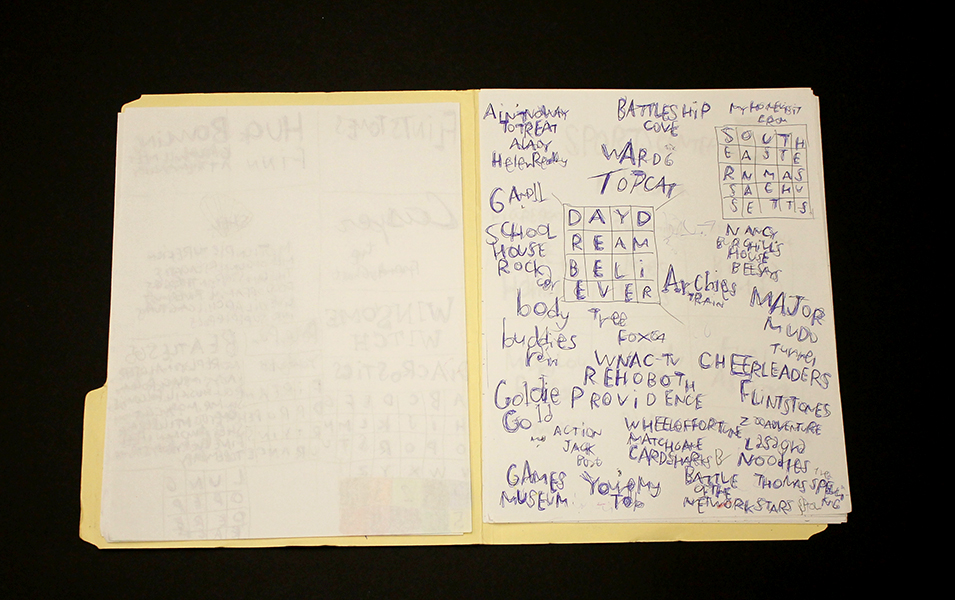

Untitled, ballpoint pen and crayon on paper, circa 2013 12 x 9 inches

Roger Swike's ten crayons

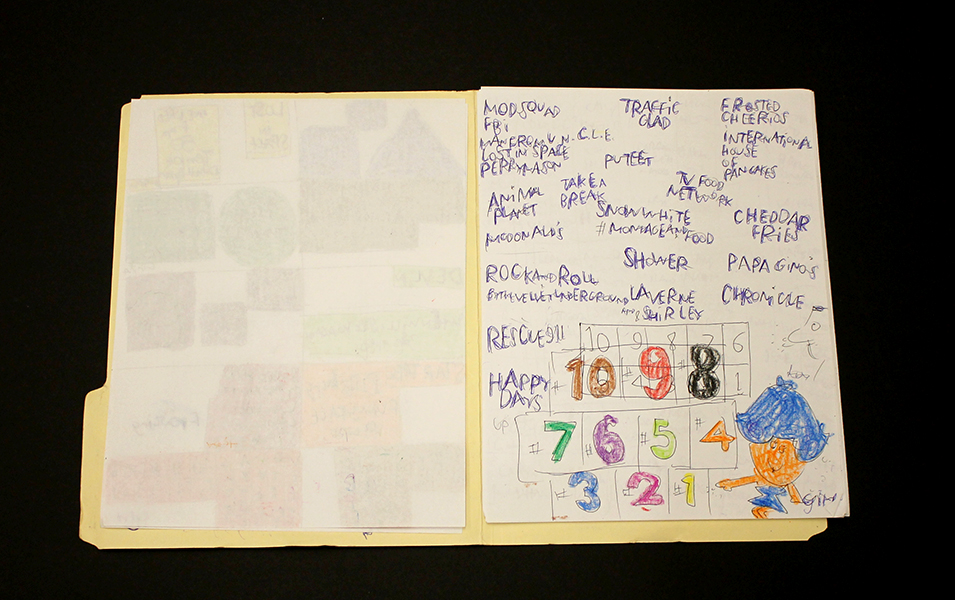

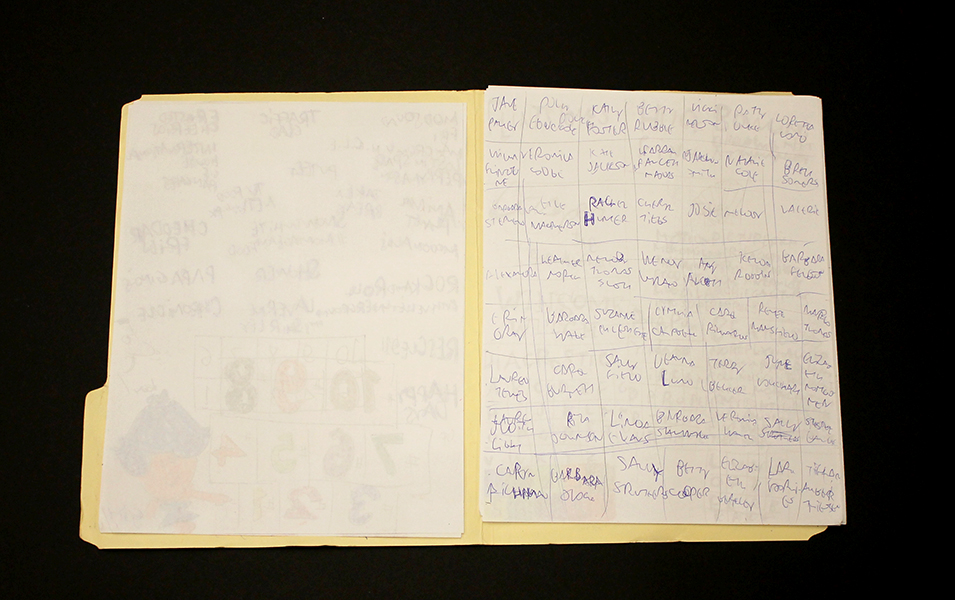

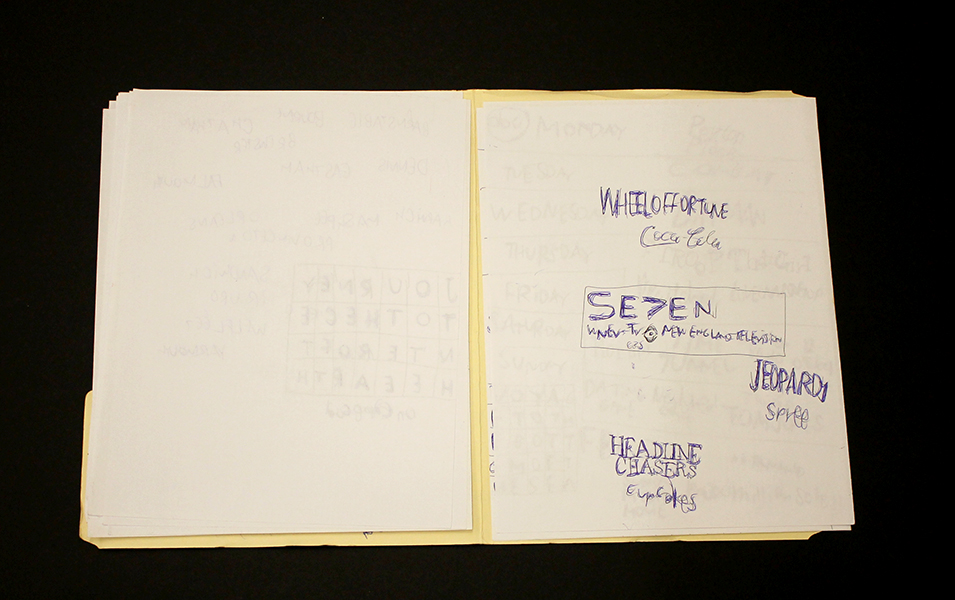

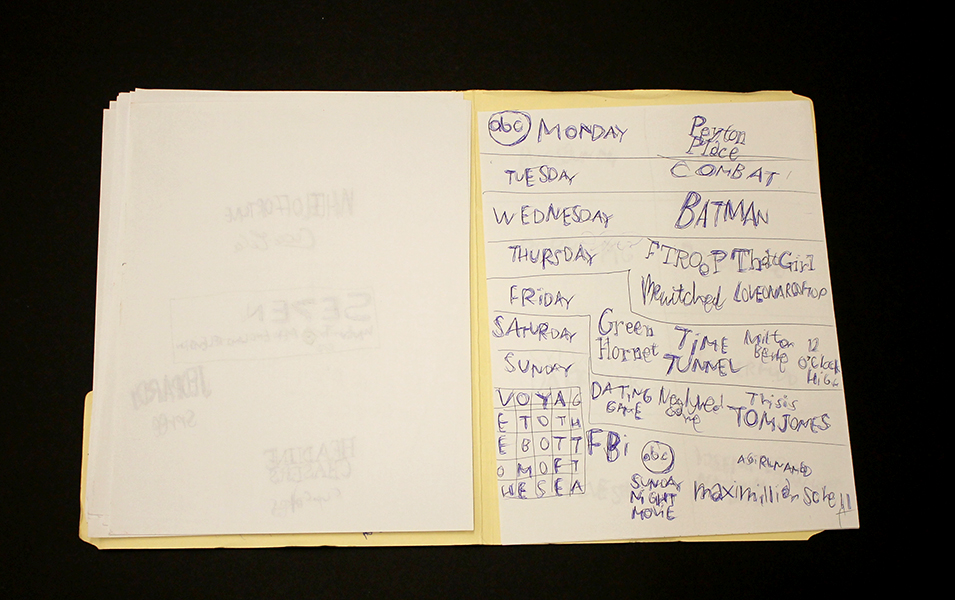

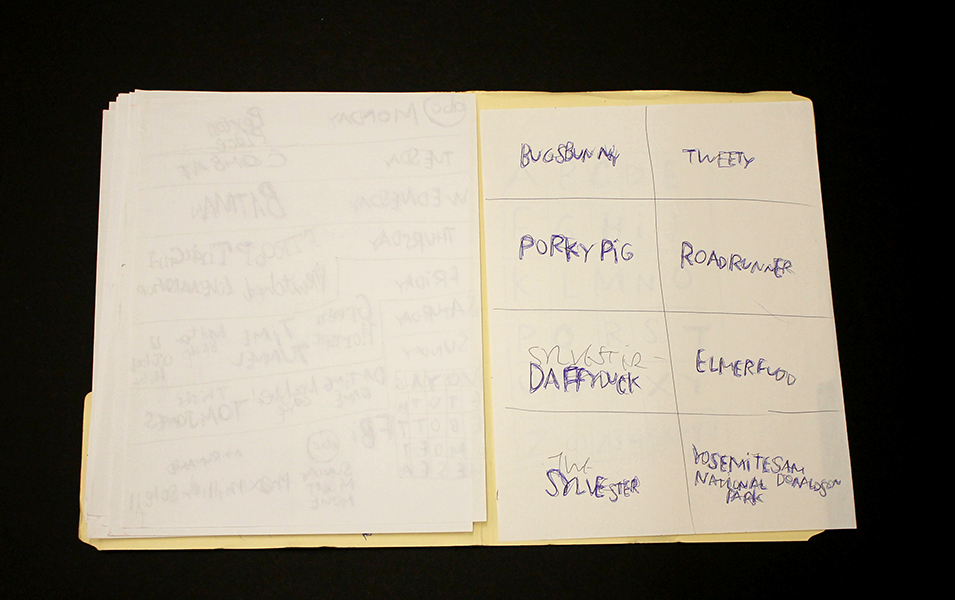

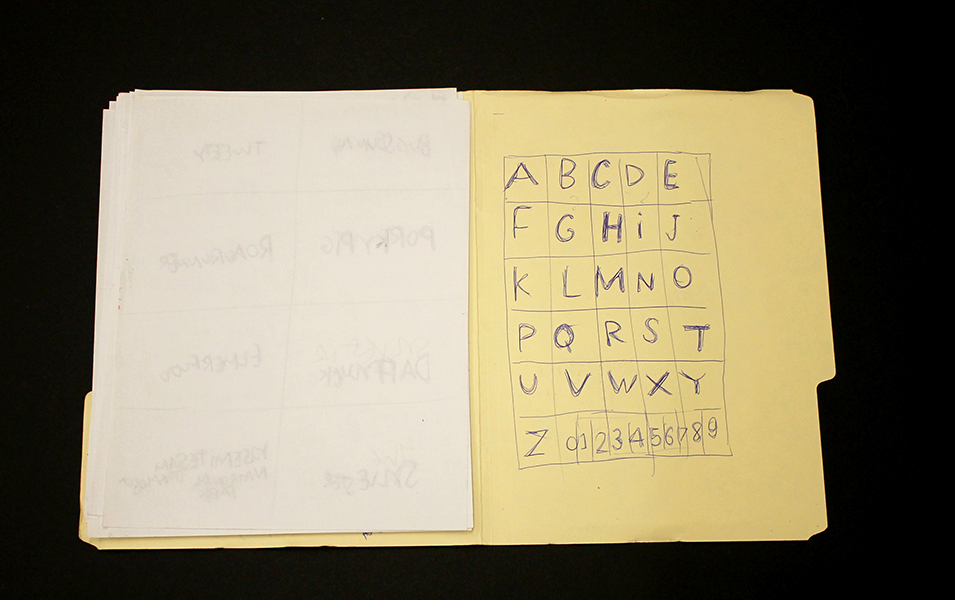

Roger Swike is an exceptionally prolific artist who works rapidly on many pieces simultaneously; much like Melvin Way, his drawing process channels an immediate and intuitive stream of information, yet is also executed with deliberation and great intention. Swike will often revisit drawings created at different times and deliberately organize them into various color-coded folders; the resulting works are an assertive, endearing proposition about what an art object can be. Within content that initially appears chaotic or arbitrary, familiar text referring to pop culture and the exterior world is pervasive. Black and blue ballpoint pens and ten crayons are utilized as though each tool has a symbolic role. Some ideas are organized neatly into grids, others are written in less regimented clusters or lists, primarily in multiple layers of ballpoint pen. Over time, curious relationships and subtle patterns emerge, such as references to the number 7 or numbers listed on their own counting down from ten (but when listed alongside the alphabet they ascend from 0 to 9).

Because Swike’s work is disciplined and systematic, the viewer is tempted to decipher the rigid system that defines it, but the true nature of the work seems to reside in the plasticity of its rules. A grid listing Loony Toons characters deviates from the pattern to include "YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK SAM DONALDSON", numbers are written in black ballpoint pen without an overlapping of blue pen, words or phrases are redacted, yet the sequence and grid are still drawn using the ten selected colors…often it feels as though Swike isn't creating the system, but instead exploring it as a poet does language, both fluent and curious. Each time Swike's lexicon is revisited, it presents an opportunity to rethink its mysterious nature - possibly an archive, message, map, poem, or something else entirely.

Roger Swike’s work will be included in Mapping Fictions, a group exhibition curated by Disparate Minds writers Tim Ortiz and Andreana Donahue at the Good Luck Gallery in LA, July 9 - August 27. Swike (born in Boston, 1962) has shown previously at the Berenberg Gallery in Boston, Fuller Craft Museum, the Outsider Art Fair, Margaret Bodell Gallery, and Phoenix Gallery in New York. He has also been awarded a MENCAP award in London, England.

We first encountered Roger Swike’s work many years ago, as studio co-managers and facilitators in a progressive art studio in Nevada; we began visiting other studios while traveling (before the inception of Disparate Minds). Swike has maintained a studio practice at Gateway in Brookline, Massachusetts (the oldest progressive art studio in the US) since 1995. Despite this, his extensive body of work remains relatively unknown outside of the Boston area, possibly because the art world hasn’t quite been ready for work as contemporary and singular coming from a living, so-called outsider artist.