We first encountered Sara Malpass’ work at NIAD in her solo exhibition What Are Words For, and have included her work in our latest curatorial project Storytellers, currently on view at LAND in Brooklyn. Selections by Malpass are featured in this exhibition in order to highlight the important perspective she offers in the discussion of narrative...

Read MoreEvelyn Reyes: Ritual, Rules, and Abstraction

San Francisco-based artist Evelyn Reyes has been diligently creating robust series of minimalist drawings at Creativity Explored for the past 15 years; over this time she has consistently maintained a presence in the contemporary outsider art discourse...

Read MoreAlan Constable

Alan Constable has been creating and exhibiting work in various media for the past thirty years, including painting and drawing, but it is the extensive body of ceramic works he has formed over the past decade that has increasingly garnered attention and acclaim...

Read MoreSusan Te Kahurangi King: Drawings 1975 - 1989

Susan Te Kahurangi King’s current exhibition marks her second, highly anticipated solo show at Andrew Edlin, following the critically acclaimed debut of the New Zealand-based artist with the space in 2014, Drawings from Many Worlds. Known for her vibrant and frenetic biomorphic abstractions, Drawings 1975 - 1989 curated by Chris Byrne and Robert Heald features a lesser known series from her prolific and consistently impressive practice...

Read MoreMiranda Delgai

We first encountered Miranda Delgai’s unforgettable work on our initial trip west, during our first studio visit outside of Nevada at Hozhoni in Flagstaff, Arizona. We were able to meet Delgai and see many of her weavings in person - work that’s technically astonishing and distinctly singular. These transporting works are defined by imagery that is compelling because of its minimal, idyllic, and genuine nature, while also conveying conceptual elements of materials rooted in tradition and storytelling that Delgai has a direct connection to through her heritage.

Delgai was born in Ganado, Arizona on a Navajo reservation in 1969, the daughter of a schoolteacher and medicine man. Delgai has maintained a prolific studio practice at Hozhoni since 1995, working in various media including ceramics, drawing, painting, and embroidery, but favors weaving. She uses Navajo-Churro wool woven on a traditional Navajo upright loom, reflecting the rich history of weaving in her community and family (who are well-known locally as traditional rug weavers).

Ella Earl, Miranda’s mother, elaborates on the presence of weaving in their immediate family history:

She has both maternal and paternal grandmothers who wove Navajo rugs as well as several aunts and cousins. Miranda’s maternal grandmother, Annabell Earl, specialized in several style of rugs double weave saddle blankets, and Wide Ruins and Klagetoh designs. She used wool from her own flock of sheep and prepared the wool from shearing the sheep, the many steps of making the wool to yarn, and collecting natural dyes that created the awesome natural colors of the yarn. Annabell and her sister at times would combine their talents on the exceptionally larger rugs. One comes to mind, a chief’s blanket at 8’ x 12’ which took them approximately six months. Miranda witnessed most of her grandmother’s activities as a child, and her grandmother never tired of explaining what she was doing. I’m sure as young as Miranda was at that time, she still remembers a lot. Her paternal grandmother, Helen Dalgai, is a weaver of rugs and she also makes sash belts which is done on a loom almost like a rug. Mrs. Dalgai specialized in the Ganado style of rugs, and she too prepared the wool from her own sheep from start to finish.

Navajo weavings are executed from bottom up on an upright loom that has no moving parts; the warp is one continuous length of yarn, that does not extend beyond the weaving as fringe. Unlike traditional Navajo weaving designs which are primarily based in pattern and fourfold symmetry, her work is more akin to the pictorial Navajo weavings of Mary Kee or the Begay family. Delgai constructs a highly personal narrative by depicting imagery from experience and memory, detailing her daily activities, interests, or recollections of family life on the reservation in Ganado; present are birds, domestic landscapes, occasional figures, and sheep. The recurrence of sheep in her work is significant, considering their prominence in the Diné (Navajo) culture:

Diné philosophy, spirituality, and sheep are intertwined like wool in the strongest weaving. Sheep symbolize the Good Life, living in harmony and balance on the land. Before they acquired domesticated sheep on this continent, Diné held the Idea of Sheep in their collective memory for thousands of years...In the high deserts and wooded mountains of Diné Bikéyah (Navajo Land), Diné pastoralists developed the Navajo-Churro breed, which assumed a central role in the People’s psychology, creativity, and religious life. With songs, prayers, and techniques taught to them by Spider Woman and looms first built by Spider Man [using sky, earth, sun rays, rock crystal, and sheet lightning], traditional Navajo weaving evolved to utilize the special qualities of the glossy Navajo-Churro wool. source

Delgai’s work proclaims not only a technical prowess with this medium, but also the joy of making. Focused and committed in her practice, she meticulously works on one piece with few interruptions until it reaches completion (usually spending 8 hours a day, 5 days a week in the studio). The process of weaving is an inherently repetitive and intensive endeavor; inevitably, Delgai’s pieces evoke the virtues of labor, time, and dedication to hand craftsmanship.

Anni Albers articulates fundamental concepts and methods surrounding this medium in On Weaving:

The horizontal-vertical intersecting of these two separate systems of thread is of great consequence for the formative side of weaving. The more clearly this original formation is preserved or stressed in the design, the stronger the weaving will be in those characteristics that set it apart from other techniques. Just as a sculpture of stone that contents itself to live within the limits of its stone nature is superior in formal quality to one that transgresses these limits, so also a weaving that exhibits the origin of its rectangular thread-interlacing will be better than one which conceals its structure and tries, for instance, to resemble a painting. Acceptance of limitations, as a framework rather than a hindrance, is always proof of a productive mind.

There is endless potential for experimentation and design within the limitations of the grid, so weaving requires much planning in order to achieve the desired visual outcome. Delgai creates a preliminary drawing in color, which she places behind her loom as a visual aid, but isn’t rigid in its translation; she has an improvisational approach to imagery and color choices while working, indicating an incredibly intuitive and skillful relationship with this slow and systematic process. Delgai has a natural ability to balance both the complex structure and flexibility inherent in weaving, successfully allowing the material to “just be” within this system, indelibly marking the object as hand-made.

The viewer is drawn in to closely examine the surface of the weave and rewarded by Delgai’s intricate work. Each work openly exhibits the origin of its making; the weft often wavers and is quite exaggerated, causing imagery to distort and shift perspective (at times verging on abstraction). Glitches and striations emerge in deceptively simple compositions, highlighting the identifiers of her inventive, idiosyncratic vision - a sheep with five legs, birds perched on a corn stalk in her unconventional re-interpretation of the Tree of Life design, or the placement of a horizon line that is both an elegant expression of the vertical weaving process and the southwest desert landscape in which she lives.

Problematically, most research of Native American traditional arts has been dominated by an anthropological discourse rather than an art historical one, without an emphasis on technical or artistic excellence. As a result, much of the work has been presented at encyclopedic museums in a manner that perpetuates a static history and colonialist point of view. Only recently have some installations started to reflect a more accurate, contemporary context. Much like Jeffrey Gibson or Wendy Red Star, Delgai is an artist whose work is grounded in identity, place, an authentic current experience, and liberated processes - a definitively contemporary perspective that transgresses the expectations of a Native American aesthetic and the traditional.

Mapping Fictions: Daniel Green

Daniel Green, Fifteen People, 2009, Mixed media on wood, 14.25 x 22.5 x 1.75 inches

Daniel Green, Little Mac vs Soda Poponski, 2015, mixed media on wood, 11.5 x 15 inches

Daniel Green, The Sun, 2015, mixed media on wood, 6 x 16.5 x 1 inch

Daniel Green, Business Delivery, 2011, Mixed media on wood, 13 x 29 x 1 inches

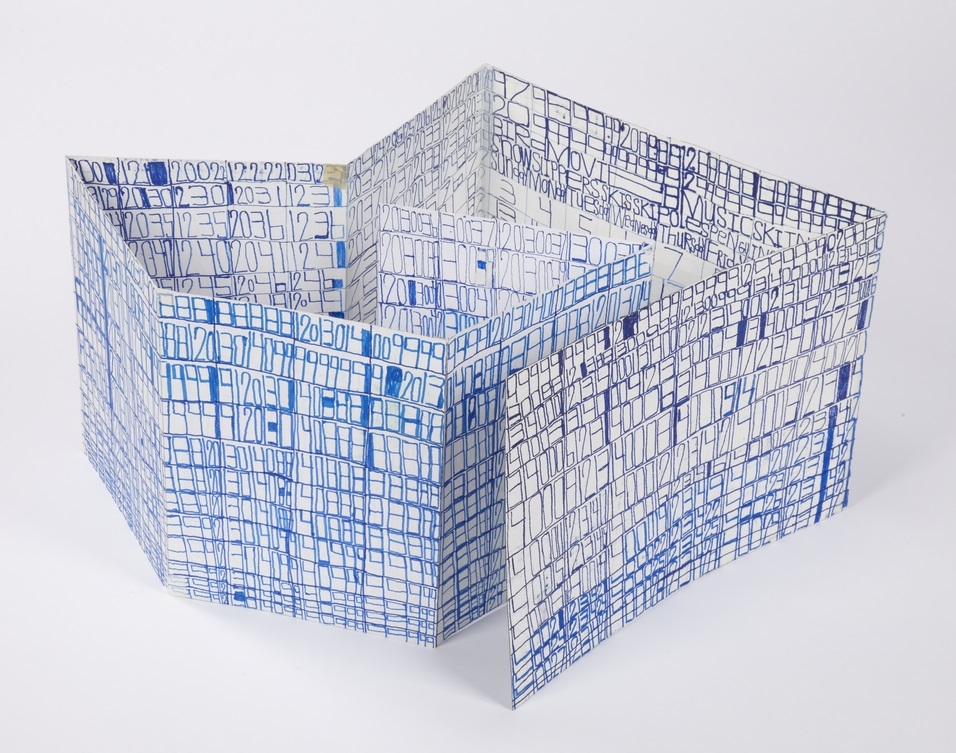

Daniel Green's process is slow and intimate; quietly hunched over his works in the bustling studio, he draws and writes at a measured pace. These detailed works are an uninhibited visual index of Green’s hand; when read carefully, they become jarring and curious, slowly leading the viewer to meaning amid the initial incoherence. Green’s text is poetic and complex - language and thought translated densely from memory in ink, sharpie, and colored pencil on robust panels of wood. Figures and their embellishments are drawn without a hierarchy in terms of space occupied on the surface; they are at times elaborate and at other times profoundly simple. The iconic figures’ facial expressions (Jesus, Abraham Lincoln, Tina Turner, video game characters, etc.) are generally flat with proportions stretching and distorting subject to Green’s intention.

Ultimately, these drawings compel the viewer to internalize and decipher Green’s ongoing, non-linear narrative. His drawings call to mind Deb Sokolow’s humorous, text-driven work, but are less diagrammatic and concerned with the viewer. In an interview with Bad at Sports’ Richard Holland, Sokolow elaborates on her process:

I’ve been reading Thomas Pynchon and Joseph Heller lately and thinking about how in their narratives, certain characters and organizations and locations are continuously mentioned in at least the full first half of the book (in Pynchon’s case, it’s hundreds of pages) without there being a full understanding or context given to these elements until much later in the story. And by that later point, everything seems to fall into place and with a feeling of epic-ness. It’s like that television drama everyone you know has watched, and they tell you snippets about it but you don’t really understand what it is they’re talking about, but by the time you finally watch it, everything about it feels familiar but also epic. (Bad At Sports)

Much like Sokolow, Green engages in making work that begins with the rigorous practice of archiving information culled from his surroundings and interests, which then develops into intriguing, fictitious digressions. Dates and times, tv schedules, athletes, historical figures, and various pop culture references flow through networks of association - “KURT RUSSEL GRAHAM RUSSEL RUSSEL CROWE RUSSEL HITCHCOCK AIR SUPPLY ALL OUT OF LOVE…” Although the listing within his work sometimes gives the impression of being intuitive streams of consciousness, most of it proves to be very structured and complex within Green’s system. Rather than expression or even communication, the priority seems to be the collection of information or organization of ideas; the physical encoding of incorporeal information as marks on a surface is a method for making it tangible, possessable, and manageable.

Daniel Green, Pure Russia, 2011, Mixed media on wood, 9 x 23 x 3.5 inches

Pure Russia (detail)

From the perspective that Green invents, there’s an endless number of time sequences that haven’t been considered before. A grid of days and times (as in Pure Russia) imagines time passing in increments of one day and several minutes, then returns to the beginning of the series, stepping forward one hour, and proceeding again just as before. It could be cryptic if you choose to imagine these times having a relationship to one another, or it could instead be an original rhythm whose tempo spans days, so that it can only be understood conceptually as an ordered structure mapped through time - the significance of the pattern superseding that of specific moments.

By blurring the distinction between the articulation of ideas through text and the development of mark-making, Green’s highly original objects become unexpectedly minimal and material, yet simultaneously personal and expressive.

Daniel Green’s work will be included in Mapping Fictions, an upcoming group exhibition opening July 9th at The Good Luck Gallery in LA, curated by Disparate Minds writers Andreana Donahue and Tim Ortiz. Green has exhibited previously in Days of Our Lives at Creativity Explored (2015), Create, a traveling exhibition curated by Lawrence Rinder and Matthew Higgs that originated at University of California Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (2013), Exhibition #4 at The Museum of Everything in London (2011), This Will Never Work at Southern Exposure in San Francisco, and Faces at Jack Fischer Gallery in San Francisco.

Knicoma Frederick

Knicoma Frederick, Untitled (Candle Army Eyes) from the Series 80 Bit, 2006, Acrylic on canvas, 24” x 18”

Knicoma Frederick, Glory News Article from the Series Information 1600, 2012, marker and pen on paper, 8 ½” x 11”

Knicoma Frederick, Untitled (Elaborately Painted Pedicure) from the Series 80 Bit, 2008, colored pencil on paper, 8 ½” x 11”

Knicoma Frederick, from the series Die Evil 82, 2013

Knicoma Frederick, Unitled (Couple Painting/Interior) from the Series 80 Bit, 2010, Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 24 inches

“The painting is not on a surface, but on a plane which is imagined. It moves in a mind. It is not there physically at all. It is an illusion, a piece of magic, so what you see is not what you see … I think that the idea of the pleasure of the eye is not merely limited, it isn’t even possible. Everything means something. Anything in love or in art, any mark you make has meaning and the only question is ‘what kind of meaning?” - Philip Guston

Prolific visionary Knicoma “Intent” Frederick has lived the intensely dedicated life of an artist for whom painting is more than painting - it’s a way to access something deeper than merely tangible or social ends. Frederick’s work engages the practice of image design and creation with a mystical or prophetic intent, relying on and striving to access and utilize the magic inherent in the process of painting.

Sometimes remarkably akin to the work of William Scott, Frederick’s work possesses an abundance of idealism, realized as utopian visions of the future - proclamations from Glory News, superhero first responders defeating armies of demons, or a “love and justice” rocket ship flying overhead. Where Scott has a steadfast tone of praise and celebration, however, Frederick’s narrative works also include darker, stranger, sometimes ominous themes that afford them a sense of gravity, conflict, and romance.

Knicoma Frederick, Untitled (Couple Painting/Beach Scene) from the Series 80 Bit, 2010, Acrylic on canvas, 36" x 24"

Works such as Untitled (Couple Painting/Beach Scene) live in a space characterized by a more cryptic sort of mysticism, in which painting becomes not only the method that Frederick employs, but also becomes incorporated into the content of the image - overtly, when paintings are included in the image, and less explicitly when “painting” as an archetype is present in the work via the presence of painting tropes (such as a dramatic seascape or elements of traditional still life). These tendencies also present themselves in the work of Los Angeles based painter John Seal.

In response to our inquiry about Frederick and the concept of paintings of paintings Seal remarked:

"The magic, really, is in the disconnect/misconnect. It is in the way the subject and its material delivery interface/intermesh with the viewer's life experiences--it is the surprise of finding anything in common, the surprise of seeing one's self, altered and new, reflected in the painting which in turn becomes new in the viewer's eyes. The magic is in this dual rebirth of viewer (subject) and painting (object). The magic is the painting's ability to make this dual rebirth visible. Painting paintings of paintings is, to me, a way to lead people into the mechanics of image, and to invite the viewer to examine their own relationship to looking: if a picture can be captured by a picture via the means (language) of painting, what can it do to the rest of the world?"

Knicoma Frederick harnesses these mechanics to not only compel the viewer to reflect on the capacity of painting, but to also assert the presence of his message in the world he envisions. The "dual rebirth" that painting facilitates is, for Frederick, a pathway into this realm that his work manifests, and painting is explicitly the magic by which this manifestation takes place.

In the course of discussing his WPIZ series of artist books, and a fictional video game called ArtFighter (which exists within WPIZ) Frederick articulates his manipulation of this mystical function of painting:

"People have heard of games like ‘Street Fighter’ and ‘Mortal Combat’ and ‘Tekken’ for PlayStation and XBox and all of those different types of game systems…But ‘Art Fighter…is fighting with artwork. You’re taking artwork and you’re fighting the situation with it. You’re taking a picture that represents what you want to have happen, done by the storyline in each book. You’re taking a picture, and you’re destroying the negative with it…I have an obligation to make the WPIZ so that the books are used for overcoming the evil that’s in the people’s way." (source)

Shortly before the establishment of the Creative Vision Factory (where Frederick maintains his studio practice), Director Michael Kalmbach encountered Frederick attempting to get permission at a drop-in mental health center to use the copy machine (unsuccessfully), presumably for the distribution of a handwritten series of newspapers (in the neighborhood of six hundred pages). Kalmbach cites this event as instrumental in the development of CVF (informing its goals, design, and function), not only due to the magnitude of this endeavor, demonstrating the need for and potential value of a studio of this kind, but also that the content of these newspapers provided important insight about both Frederick's personal experience and the mental health system in general.

Frederick’s works are conceptualized as series of books for which each work represents a specific page. Over the four years that he has been with CVF, he has published more than 25 artist books, each comprised of 125 - 150 works; prior to the publishing a book, the works can not be sold individually. Frederick has an extremely productive creative practice; Kalmbach estimates that he creates roughly 1000 works per year.

Knicoma Frederick is originally from Brooklyn, New York, but is currently based in Wilmington, Delaware. Recent exhibitions include All Different Colors and Outsiderism at Fleisher/Ollman in Philadelphia and previously at numerous venues in Wilmington, Delaware. He has work in the permanent collection of the Delaware Art Museum and is the recipient of an Emerging Individual Artist Fellowship from the Delaware Division of the Arts.

Courttney Cooper

Cincinnati Map, 2010, ballpoint pen on collaged paper, 64" x 88"

Untitled, 2015, ballpoint pen on collaged paper, 52" x 80"

Cincinnati Map, 2009, ballpoint pen on collaged paper, 51" x 85"

Cincinnati Map, 2009 (detail)

Cincinnati Map, 2009 (detail)

images courtesy Western Exhibitions and Visionaries + Voices

Cooper’s oeuvre is a ongoing narrative featuring Cincinnati, imparted with adoration and idealism. Drawings that are tenaciously committed to archiving the city’s developing reality in bic ballpoint pen, Cooper documents the destruction of old buildings and construction of new ones, while modifying details to reflect the time of year (often after they've been hung in an exhibition space). But they are also richly populated with celebratory, idealistic imagery - flags flying on rooftops, hot air balloons traversing the sky above the river, “Do not be afraid, be a precious friend! Zmile, you’re in Zinzinnati Ohio USA 2011”.

Cooper’s works are often characterized as maps, which isn’t an entirely accurate categorization. Visionaries + Voices’ Krista Gregory points out:

I've come to learn that Courttney has been drawing "aerial views" of Cincinnati since he was a small child, first using an etch-a-sketch. His mark-making certainly reflects having this type of information/tool...I see the work that Courttney creates more in the vein of landscape, or townscape; as they are romantic in their visceral love for this place...I think that this work being categorized as ‘maps’ is misleading and couches them in something that is more related to Courttney's disability rather than to what it is that he is actually expressing and creating. They are not accurate. They are not drawn completely from memory. I've witnessed people hold on to wanting to think these things because it makes the work accessible or novel in some way. I sort of think that it is a reductive way to see them

The desire to see Cooper’s works as maps may be the consequence of trying to categorize autistic thinking - relegating autistic artists as spectacles of savant-ism. Courttney Cooper, however, is not comparable to Stephen Wiltshire, for example; his drawings are not an accurate configuration of streets as a road map indicates, nor are they a repetitious anonymous depiction of a city in an illustrative way. They're indeed informed by an intimate experience with his city - an astounding wealth of information accumulating across increasingly massive surfaces (created by gluing together scrap paper that Cooper gathers while working at Kroger). But this isn't the subject of the work, it's only the formal foundation that serves as a vehicle for Cooper’s voice. Cooper’s drawings are a complex and authentic network of specific places and structures; his streets are composed of details from memory or observation, cataloging expressions of particular perceptions in particular moments. The relationship of these moments to each other in space is approximated, as in memory - all of which culminates in a dizzying realm of overlapping information that becomes a living record, adorned generously with nostalgic, commemorative expressions of community and identity.

Zinzinnati Ohio USA: The Maps of Courttney Cooper curated by Matt Arient, is a selection of Cooper's drawings from 2005 - 2015, currently on view at Intuit through May 29th. Cooper is represented by Western Exhibitions in Chicago, where he has an upcoming solo exhibition November 12 - December 31, 2016. Cooper has maintained a studio practice at Visionaries + Voices in Cincinnati since 2004; he has exhibited extensively in the greater Cincinnati area and has work in the Cincinnati Art Museum collection. Selected exhibitions include the Wynn Newhouse Exhibition at Palitz Gallery, Syracuse University (as a 2015 Wynn Newhouse Award recipient), Cincinnati Everyday at the Cincinnati Art Museum, Maps + Legends: The Art of Robert Bolubasz and Courttney Cooper at Visonaries + Voices, Studio Visions at the Kentucky Museum of Art, Cincinnati USA: Before Meets After at PAC Gallery, and Indirect Observation at Western Exhibitions.

Sylvia Fragoso

Untitled, glazed ceramic

Untitled, glazed ceramic, 14" x 7" x 7", 2013

Untitled, glazed ceramic, 17" x 11" x 11", 2015

Untitled, glazed ceramic, 15" x 8" x 5", 2014

all images courtesy NIAD

Sylvia Fragoso’s methodically hand-built sculptures are crafted with a deceptive indelicacy and thick layering of glazes - small monuments in which form is defined by seeking rather than devising. Much like the ceramic work of Sterling Ruby or Julia Haft Candell, Fragoso reaches a compromise between concept and process. Where opportunities arise, she inserts symbolism that declares an identity for the work; subjects common in her drawings such as church and family are translated into physical form in a manner analogous to the way that her method of building with clusters of shapes on paper translates to her process of building with clay. References to function or representation are ultimately denied in favor of material manipulation and aesthetic - a revelation of the joy of making.

In a recent Art In America article The Happy Medium, Leah Ollman discusses the re-emergence of ceramics in the contemporary art discourse (especially in L.A.):

A new shift, roughly a decade old, has been catalyzed not by a single or even a few strong personalities, but by a broader redefinition and realignment of creative practice. Increasingly post-disciplinary, artists roam freely among mediums, unencumbered by traditional boundaries and hierarchical divisions. Many show a renewed interest in work of the hand, which they see as an antidote to theory- and concept-driven art. A messy physicality is often their (defiant) answer to the disembodied digital; theirs is a rising constituency for authenticity which advocates the material over the virtual.

This shift has extended to progressive art studios as well; in addition to Fragoso, other self-taught artists creating exceptional ceramic work are Mirov Menefee of The Canvas in Juneau, Alan Constable and Chris Mason of Arts Project Australia in Victoria, Cameron Morgan of Project Ability in Glasgow, Tanisha Warren at Creative Growth in Oakland, and Billy White, also of NIAD.

Fragoso (b. 1962) has exhibited recently in Hold Onto Your Structure : The Ceramics of Sylvia Fragoso at NIAD Art Center (2016), Telling It Slant organized by Courtney Eldridge at the Richmond Art Center (2015), Visions et Créations Dissidents at Musée de la Création Franche in Bégles, France (2014), ArtPad SF at the Phoenix Hotel in San Francisco (2013), and extensively in group exhibitions at NIAD, where she has maintained studio practice for many years.

Untitled, graphite on paper, 24" x 18"

Deveron Richard

Sectra Shower, watercolor on paper, 18" x 24”, 2014

The Milkets, watercolor on paper, 26" x 32”, 2015

The Planets, watercolor on paper, 17.25" x 23.5”, 2009

A Border Between Unicorns, watercolor on paper, 19" x 25.5”, 1996

Deveron Richard maintains a creative practice at one of many ECF art centers in the LA area (previously discussed by Disparate Minds in terms of their relationship to DAC Gallery). His inaugural solo show is currently on view in LA at the Good Luck Gallery through May 21st. From the Good Luck Gallery:

“An idiosyncratic iconography of visionary space travel and anthropomorphic sexuality arrives via the South Bay of Los Angeles through the singularly fertile imagination of Deveron Richard. Winged horses in brassieres and high heels glide peacefully around the cloud-enshrouded towers of a futuristic city, polar bears in lipstick and slit dresses prance through a fluorescent arctic landscape, and provocatively-attired unicorns face off on a hallucinatory geometric color grid. These hybrid creatures of exaggerated femininity exude a quirky eroticism. Rendered in watercolor with a distinctively saturated palette, inventive draftsmanship and hypnotic backdrops of complex rhythmic patterning. Other works depict interplanetary battles with rockets hurtling through galaxies and deadly beams shooting into space.”

Marvin Asino

From the Disparate Minds collection: “For all of my friends and one basketball player” is a zine containing 21 poems interpreted from the text works of Marvin Viloria Ariza Asino. It’s sensibility can be described using Marvin’s own words “rhythm; kind, beautiful, friendly.” Asino writes in a matter-of-fact manner (siding in a space where humor and simple, profound truths meet), so the force of its beauty comes entirely by surprise with a wonderful sense of mystery.

This anthology was given in the course of a conversation with one of Marvin’s many friends, Robert Grey, at Full Life, in Portland Oregon last year. An updated overview of Full Life, a very different kind of program, will be posted soon.

Billy White

My Body, mixed media on canvas, 18" x 24", 2015

Jed Clampett, glazed ceramic, 10" x 7" x 4"

Untitled, acrylic, 18" x 24", 2015

Untitled, graphite on paper, 12" x 17"

Untitled, mixed media on canvas, 24" x 18"

The process of evaluating any artwork includes some interpretation of how it functions - mechanisms such as the way gestural brushstrokes communicate movement by indexing the physical action of their application, or the way that arrangements of representational imagery can imply relationships between elements that generate narrative.

The mechanism by which Billy White’s paintings elicit emotion is sharply specific, yet escapes analysis, remaining a wonderful mystery. A loose, fearless application of paint renders forms with a striking physicality and sense of humor. There’s an uncanny affinity with the work of figurative painters Todd Bienvenu and Katherine Bradford (who both have an aesthetic undoubtedly informed by the work of self-taught artists). The impact of White’s work cuts through a vivid alternate world that operates on White’s terms - a highly original set of priorities, passing over image and rendering to achieve an expression of mood and vitality, as though excavating the underlying stories that were already present; impatient mark-making and barely legible imagery find time and space for redolent storytelling and detail. While he typically focuses on painting and drawing, White occasionally creates small ceramic sculptures that are rich in character and evocative of Allison Schulnik’s warped clay figures - slumped postures, elongated, rubbery appendages, intermingling glazes, and sunken, cartoonish expressions.

White’s work is largely influenced by his avid interest in pop culture, often depicting actual and imagined events in the lives of various celebrities or fictional characters, from Dr Dre to Hulk Hogan to Superman. NIAD provides some insight into White’s process: “He might start off painting Bill Cosby, but quickly change his mind by lunch. When that happens, he simply works right on top and doesn’t erase what came before. The new work becomes an extension of the old. By the end of the day this could happen several times and what’s often left is a latticework of figures and stories with interchangeable meanings.”

Billy White (b. 1962) has exhibited previously in Rollergate at the Seattle Art Fair, Telling It Slant organized by Courtney Eldridge at the Richmond Art Center, Undercover Geniuses organized by Jan Moore at the Petaluma Art Center, ArtPad San Francisco at the Phoenix Hotel, and extensively at NIAD Art Center, where he has maintained a studio practice since 1994. He has an upcoming solo exhibition at San Francisco’s Jack Fischer Gallery later this year.

Julian Martin

Untitled (motorbike), pastel on paper, 15" x 11", 2014

Untitled (White on Cream), pastel on paper, 15" x 11 1/4", 2010

Untitled (Orange Shape and Khaki), pastel on paper, 15" x 11 1/4", 2010

Untitled (parrot), pastel on paper, 15" x 11", 2014

Like other progressive art studio artists at the Outsider Art Fair, Julian Martin works from found imagery culled from magazines (often art publications). Whereas Helen Rae pushes found imagery to greater levels of complexity and reality, and Marlon Mullen and Andrew Hostick retell images in their own vocabularies, Martin pares the image down to a series of perfectly resolved moments in which a series of forms (each powerful and resolved in their own right), is described with an abundance of velvety pastel marks applied deliberately and seamlessly with a deft touch. Martin achieves a ubiquitous softness - soft colors, shapes, surfaces, and materials, yet always precise and controlled in application, saturating the surface while maintaining the boundaries of each form with conviction.

Initially, Martin’s work seems aesthetically akin to the work of many young artists currently revisiting concepts of early abstraction with suggestions of the figure, such as Brooklyn-based painters Austin Eddy and Tatiana Berg. However, where these artists revisit and re-imagine the ideas of artists like Picasso and Dubuffet, who were themselves appropriating the aesthetics of outsiders, Martin is the real thing. Not in that he is a “real outsider” (at this point Martin is quite well established professionally, certainly as much an insider as any artist living and working in Melbourne), but rather that his works, in sum, lack any tone of irony or nostalgia; the strength of resolution that each of Julian Martin’s drawings finds is achieved through a minimalist’s sensibility, preoccupied with the absolute rather than a historical context, more comparable to Malevich, Gottlieb, or Mondrian than Cubism or Art Brut.

The proposition underlying Martin's work seems to be that a found image may, inevitably or inherently, possess a more perfect resolution that can be exposed through a measured and thoughtful process of reduction. Unlike Mondrian, the absolute is not found in total abandonment of the original, but in the poetic and specific distillation of the identity and expression of the image.

Martin has attended Arts Project Australia in Melbourne since 1988 and has exhibited extensively at various venues in Melbourne since 1990. He has also shown previously at Fleisher/Ollman (Philadelphia), several Outsider Art Fairs (NYC), Museum of Everything (London), MADMusée (Belgium), Phyllis Kind Gallery (NYC), Jack Fischer Gallery (San Francisco), among others. Martin is represented by Fleisher/Ollman and Arts Project Australia.

The Effortless Humor of Michael Pellew

Michael Pellew, Untitled, 2016, Mixed Media on Paper, 11"x17"

Michael Pellew, Michael and Latoya Texting on the Beach, 2015, Acrylic on Canvas, 12"x9"

Michael Pellew, British Platter, 2015, Mixed Media on Paper, 14"x17"

One of the fantastic surprises at the Outsider Art Fair this year was our experience with the work of Michael Pellew. Pellew’s work is unassuming, and in the context of the fair particularly blends in - a style defined by repetition, drawing within a simple system, and the use of unconventional materials (markers). We were more familiar with his series of small original drawings marketed as greeting cards, which typically feature a grouping of four or five figures (available at Opening Ceremony in Manhattan and LA). In a larger scale, the voice only available in snippets in smaller works unfolds to become an astonishing comedic performance.

The repetition and economy of visual language in his work is necessary to the humor - each figure articulated in an identical manner, with just a few distinctive features describing its specific identity. The supreme ease with which each character enters the scene via this agile visual vernacular accounts for the works’ pace and timing. There's an exciting cleverness in the way the simple archetype of the figure takes on the identity of countless celebrities, analogous to a skilled impressionist mimicking pop culture icons in rapid succession. Pellew seems to be compiling an ongoing, shifting catalog of celebrities; those with apparent relationships or categorizations are sporadically interrupted with unexpected pairings (Princess Diana and Lemmy Kilmister) or fictional personas (Lauryn Hill M.D. from Long Island College Hospital, The Phanton Lord). Viewers with an extensive knowledge of pop culture are highly rewarded by the ability to recognize the abundance and subtlety of his references.

Michael Pellew, Untitled, 2015, Mixed Media on Paper, 22"x30"

Humor is an important element in many works that don't necessarily make us laugh, but truly funny art like Pellew’s (beyond the occasional clever moment or inside joke), is very uncommon. Crystallizing the elusive and ephemeral quality of comedy into a permanent art object is extremely difficult to achieve. Usually the most overtly funny approach is to employ an explicit punchline that rests on an impressive technical or procedural spectacle; artists that exemplify this approach are those like Wayne White or Eric Yahnker.

Eric Yahnker, Beegeesus, 2005, 13 x 10 x 10 in.

"Bible whited-out except that which sequentially spells Bee Gees" image via www.ericyahnker.com

Pellew’s humor, however, is more nuanced, so in the absence of a punchline, his approach relies on absolute fluency rather than overt technical prowess. The quintessential example of this brand of humor is Raymond Pettibon; works that appear effortless afford the artist a more casual voice, equipped to cultivate a more dynamic interaction between the work and viewer. When it's less obvious that there's a joke present, the viewer tunes into a more acute examination of tone and timing in search of the artist's intention.

Raymond Pettibon, image via www.raypettibon.com

Whereas Pettibon uses this approach to insert sardonic or satirical moments of levity into his generally grim oeuvre, Pellew instead engages this sort of humor with a lighter and even silly sensibility; he creates an abundantly bright and positive space that is captivating. The conceptual foundation of his work becomes about treading the line between earnestly identifying as an artist, or slyly engaging in play-acting the role of an artist. Walton Ford has described using play-acting (as a scientific illustrator) in a similar way as an entry point into comedy. In Pellew’s case, the performance is broader, and in its execution more engrossing - guiding you through his alternate world, you're always uncertain if he’s serious, even as he crosses well over into the realm of absurdity.

Michael Pellew, Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 2014, Acrylic on Canvas, 14"x11"

In the affable universe he realizes, there’s virtuosity in the way moments of comedic surprise cut sharply through. The lingering experience of these pieces isn’t static, but a dreamlike memory of an event unfolding; line-ups of celebrities…everyone had a pepsi…they were all hanging out around a limousine eating McDonalds…and then Marilyn Manson is offering his famous burger and fries. It’s an alternate reality composed of familiar characters and Pellew is leading us along, introducing each of them, all in his voice - but really it's the viewer’s voice. You are left walking away amused, incredibly satisfied, but not entirely sure what has just happened.

Pellew has been working at LAND Gallery’s studio for over ten years and participated in numerous exhibitions in New York, including group shows at Christian Berst Art Brut and the MOMA. His work has been acquired by many reputable collectors, including Spike Lee, Sufjan Stevens, Citi Bank, JCrew and PAPER Magazine.

Michael Pellew, Making a Band (detail)

Mary Ann James

Heaven, graphite and watercolor on paper, 2015

Train, graphite, micron, and watercolor on paper, 2015

Camping, graphite, micron, and watercolor on paper, 2015

Untitled, graphite and watercolor on paper, 2015

Mary Ann refers to all of her works as her “creations”. Like a story teller, she’s inspired by a combination of personal experiences in her daily life and concepts that she values, such as motherhood and heaven. Consequently, her works have a narrative feel - depictions of people and places that may be part of a story.

Mary Ann’s process, however, is not guided by narrative, but rather by an ambition to create. As a result of this, her subjects aren’t rendered as two-dimensional images, but intended to exist in their own right, in a two-dimensional world. In effect, her imaginative nature inevitably imbues the world she creates with a narrative life, but this distinction in her creative practice is important. Because she's creating rather than depicting, a figure, for example, is drawn in its entirety before clothing is drawn onto it - often a layer of flesh tones is painted before a subsequent layer of paint is added for the color of their clothing. If she includes shoes or gloves for a figure, she draws them around the foot or around the hand, rather than over it. Figures standing in front of a train are placed below the train, rather than in front of it, because both the train and people are created separately. Mary Ann has a highly original way of translating her perception of reference images onto paper, often distorting the scale of objects and editing out details that don’t fit her vision.

In the world she creates, scale is an expressive choice; each form is given whatever space it needs to exist and relate to the world it occupies. Ultimately in her work, she creates people and things to stage a still, timeless moment that’s simple, complete, and good.

Mary Ann James maintains a studio practice at The Canvas, a progressive art studio in Juneau, Alaska.

Grace Coenraad

Grace Coenraad, Untitled, micron, sharpie, graphite, and india ink on paper, 2015, 16" x 16"

Grace Coenraad, Untitled, micron, sharpie, and india ink on paper, 2015, 22" x 22"

When I first painted a number of canvases grey all over (about eight years ago), I did so because I did not know what to paint, or what there might be to paint: so wretched a start could lead to nothing meaningful. As time went on, however, I observed differences of quality among the grey surfaces – and also that these betrayed nothing of the destructive motivation that lay behind them. The pictures began to teach me. By generalizing a personal dilemma, they resolved it.

Gerhard Richter, From a letter to Edy de Wilde, 23 February 1975

Coenraad’s dark, minimalist works are the product of a measured and slow process, executed with extreme diligence. Using 08 black microns, traditional pen and ink nibs, and occassionally graphite, she densely hatches careful lines, which slowly collect on the surface over many hours of work. This method is a clear path leading to an absolute resolution - the surface being obscured by black. The magic of these pieces (although they’re inextricable from the story of the steadfast execution of this simple method) lies in content that’s fantastically nuanced and complex. The black square is a subtle, jagged field comprised of various sheens and tones - certain patches are tinted by an initial application of bright watercolor (often pink or blue) that has bled through the subsequent, inevitable layer of black. The marks made using microns are incised, and those created with india ink and nib lift the paper slightly away from the surface, resulting in a textured surface reminiscent of Richard Serra’s black oil stick drawings. And much like the reductive, sublime paintings of Richter or Clyfford Still, Coenraad demonstrates that the honest act of mark-making isn’t reduced when it’s stripped of intentions or illusion. Conversely, it only becomes more revealing and mysterious.

After his first museum exhibition of entirely black drawings in 2011, Richard Serra was described by critic Roberta Smith as hermetic, abstract, difficult, and austere, an assessment that he accepted, describing it as “a virtue.” Explaining that art has to be difficult, Serra said that drawing independent of the flamboyance of color interaction, mark-making on its own, in black on white, proves to necessitate invention, thereby providing a “subtext” for how an artist thinks. For him, allover black works were a move to escape that convention of drawing as a “form to ground problem” to create works concerning “interval and space” rather than image.*

Coenraad didn’t stumble upon this principle inadvertently like Richter; for her, it’s a process that reflects a way of being. It is, as Serra articulates, an extension of the thought process and more. To a degree that’s rarely seen for non-performative artists, Coenraad is an artist for whom the boundary between life and art is blurred. Every task is executed with the same resolute sensibility, engaging life with a singular and sophisticated method in pursuit of perfection. Every bite of food is carefully selected and examined before being eaten (ingredients of an undesirable color rejected), every mundane task is afforded great consideration. For years she has worked part-time at a document destruction facility, where no one has been able to compel her to obliterate more than one document at a time. At home, blackening crossword puzzle squares for hours with ballpoint pen or sharpie is part of her daily ritual.

In the studio, Grace is fully immersed in her practice - working with her face close to the surface, she becomes absent from anything exterior of the drawing process. Occasionally she will stop and look around the room for a moment like a deep sea diver rising briefly to the surface, before submerging again. Grace doesn’t discuss her work, not because she can’t, but because there seems to be nothing necessary to say once a piece is finished.

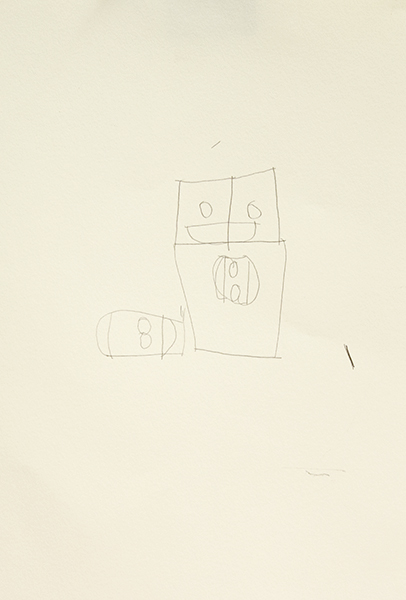

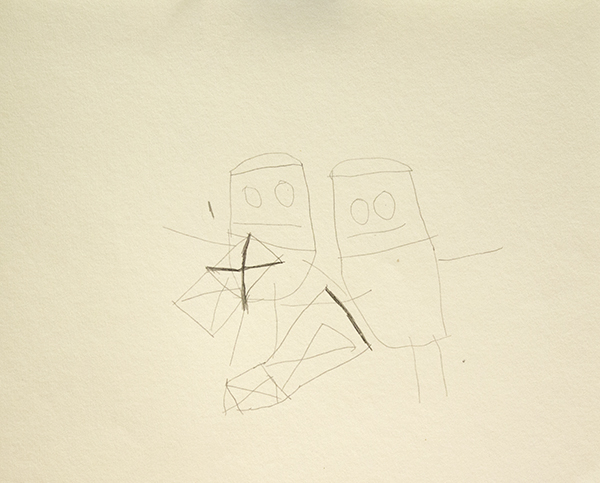

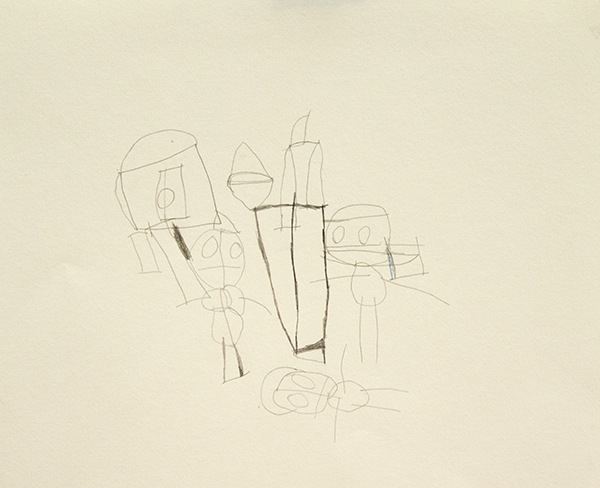

Between her larger, long-term works, Coenraad sometimes creates small graphite sketches, thoughtful experiments that serve as a point of entry into her mysterious thought process. The placement of faces demonstrate the dynamics of orientation in her drawings. The coexistence of elements in combination with turning the paper many times while working isn’t incidental to the process, but essential to it.

Coenraad is a Juneau-based artist who maintains a studio practice at The Canvas in Juneau, Alaska. Her work will be included in an upcoming group exhibition curated by Disparate Minds writers Tim Ortiz and Andreana Donahue at The Canvas' exhibition space in December.

William Scott

San Francisco-based artist William Scott is a believer in a better world; his works are the celebratory announcement of the wholesome future. His complex oeuvre not only imagines a parallel universe, but Scott leads by example with a joyous conviction in articulating his vision of a utopian future San Francisco, “Praise Frisco”. Scott’s paintings, drawings, and sculptures are executed in a manner consistent with this gospel of idealism and excellence, shining with a pristine vibrance.

In a Frieze review of Scott’s solo exhibition "Good Person" at White Columns, Katie Kitamura asserts:

Scott’s work is wrapped up in the idea of what it means to be a citizen, to be interpellated within the social order. That is probably most memorably captured in an untitled series of sci-fi infused works ...These are populated with a lovely switch and change of language - ‘citi-fi’ and ‘inner limits’ and ‘whole some citizen’ - and a series of wide-eyed future citizens of the world, about to depart on airport shuttles into space.

In the most direct way, Scott communicates the way in which being part of any social order relates to pop cultural paranoia and conspiracy theories. But he also captures the deeper suspicion that we are sometimes possessed by forces beyond our comprehension.

William Scott attends Creative Growth’s studio in Oakland. Scott is widely collected and has work in the permanent collections of the MOMA and The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York.

He has exhibited recently in Groupings at Park Life Gallery (San Francisco) and previously at the Outsider Art Fair (NYC), Hayward Gallery (London), Gavin Brown’s enterprise, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (San Francisco), the Armory Show (NYC), Palais de Tokyo (Paris), NADA (Art Basel, Miami), and White Columns. From White Columns’ "Good Person" exhibition statement:

For many years William Scott has been working on an ongoing urban planning project that would see San Francisco – in Scott’s terminology – “cancelled”, only to be re-imagined, rebuilt, and rechristened as a new city named ‘Praise Frisco.’ Scott’s urban project, which was the subject of his...White Room exhibition at White Columns, is rooted in a desire to see his own socially marginalized neighborhood of Bay View / Hunter’s Point “torn down” and then subsequently renewed according to his carefully detailed plans. Scott’s ambitious, optimistic, and deeply humane project engages explicitly with San Francisco’s recent past, present realities, and potential future. (more)

John Hartman

assorted letter openers

Three Geese on Stands, Pine and Cyprus

owl sculpture, mahogany

Material in the raw is nothing much. Only worked material has quality, and pieces of worked material are made to show their quality by men, or put together to so that together they show a quality which singly they had not. “Good material” is a myth. English walnut is not good material. Most of the tree is leaf-mold and firewood. It is only because of workmanlike felling and converting and drying and selection and machining and setting out and cutting and fitting and assembly and finishing - particularly finishing - that a very small proportion of the tree comes to be thought of as good material.

- David Pye, The Nature and Art of Workmanship

John Hartman skillfully works within the tangible, tactile boundaries of a small-scale process and commitment to good workmanship. Within this intimate context, he engages wood without conceptual boundaries, exploring utility, mimesis, and sculptural invention freely. Through the tradition of woodworking, Hartman is able to realize a wide range of possessable objects that evoke a sense of elegance and great integrity.

Hartman is a Manhattan-based artist who has been working in Pure Vision’s studio since 2013. From Pure Vision:

Hartman’s “main passion is woodcarving. John was introduced to the craft at the age of eleven, in wood shop at The Rudolph Steiner School. He began by crafting a cherrywood flour scoop. Instantly drawn to the medium, he slowly started teaching himself how to make more complicated objects. Collecting rare woods from around the world such as ebony, zebra wood, Philippine mahogany and bloodwood, John now spends hours in the studio and at home carving, whittling, sanding and polishing each piece. Inspired by visits to his family’s seaside home on Fire Island, his subjects often reference birds and sea creatures.” (more)

Yasmin Arshad

Untitled, marker on paper, 22" x 30"

129999, marker on paper, 22" x 30"

Untitled, marker and acrylic on wood, 19.5" x 19.5"

Untitled, marker on paper, images courtesy Gateway Arts

Arshad’s distinctive works are characterized by series of numbers, phrases, and concepts of time that manifest in the form of visual and spacial poetry. An investigation of the overlap in the process of seeing and reading akin to Christopher Wool is present - where Wool employs the arrangement of words on a surface to disrupt the reading process systematically, Arshad’s visual and written languages instead merge more fluidly. Text forms, influenced by dynamics of color and scale, impose elusive and subjective variation in the reading experience.

Arshad’s work reflects an avid interest in ideas related to the passage of time. An invented symbol for eternity, 129999 (a single number indicating all months and years), often surfaces in her work; she also lists years chronologically beginning with the year 2000, organizing the numerical information into multi-colored grids. Over the course of 46 years, Roman Opalka painted horizontal rows of consecutive, ascending numbers (1 – ∞), an ongoing series that ultimately spanned 233 uniformly sized canvases. In “Roman Opalka’s Numerical Destiny” for Hyperallergic Robert C. Morgan writes:

From the day his project began in Poland until his death in the south of France in 2011, Opalka combined clear conceptual thinking with painterly materials. His search for infinity through painting became a form of phenomenology, which, in retrospect, might be seen as parallel to the philosophy of Hegel. Through his attention to a paradoxically complex, reductive manner of painting, Opalka focused on infinite possibilities latent within his project.

Arshad’s rigorous, repetitive approach is similar to 0palka’s engagement with infinity, yet there are more prevalent breaches in her pattern-based system. Much like the process of weaving, Arshad’s drawings reflect an intrinsic structure that serves as a guide for intended visual results, yet there is room for distortion and a spontaneous response to the surface.

Arshad (b. 1975, Florence, Italy) has exhibited previously at Cooper Union (NYC), the Outsider Art Fair, The Museum of Everything (London), Phoenix Gallery (NYC), Berenberg Gallery (Boston), Trustman Gallery (Simmons College, Boston), Drive-By Projects (Watertown, MA), Creativity Explored (San Francisco), and at Gateway’s Gallery in Brookline, Massachusetts. Arshad lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts and has attended Gateway Arts’ studio since 1996.

see more work by Arshad here

Luis Hernandez

Untitled, marker on vellum, 8.5" x 11" 2015

Untitled, marker on vellum, 8.5" x 11" 2015

Untitled, marker on vellum, 18" x 24" 2015

We were fortunate to meet Luis Hernandez at a turning point in his creative practice, as he was beginning this body of work, a series of marker drawings on vellum. Aesthetically, they’re exciting abstractions; energized and vibrant, each complex composition is perched between intuitive and systematic visual ideas. Hernandez's work effortlessly achieves what many contemporary artists currently investigating abstraction strive to, with the re-emergence of a Twombly-esque aesthetic.

Observing Hernandez in the studio, it's impossible not to feel a sense of wonder at the mysterious and dynamic nature of his prolific creative process. The contrast of expressive and systematic qualities in his work is mirrored in his disposition, which is that of an extremely earnest and affable man, with a great aspiration to speak directly and connect with the world beyond himself, but whose way of thinking and seeing is fantastically disparate from that of his neurotypical peers.

Because of his aspiration to communicate clearly, he was slow to fully embrace his instinctive practice and still sometimes strives to create representational work. When he attempts to draw from life, however, he’s never satisfied. During these moments, as he discards page after page of a sketchbook, the singularity of his experience is most clear as the renderings even he finds most successful have no obvious visual relationship to their subject. Once, an observer sympathetic to his frustration tried to assist by providing a dotted line as a guide; he has since adopted the dotted line, applying it to his abstract forms as though he can achieve a magical quality of objectivity from its presence.

In this body of work, Hernandez has described his process of drawing as moving along or searching for a path. If it’s a path, then it’s one he follows with great vigilance, a quality that he values deeply. His vigilance is a matter of faith, an inherent knowledge of the world that he believes in with great conviction; this is sometimes expressed in terms of his Tlingit heritage (referencing conversations in dreams with his ancestors or communications with Eagle or Raven) and at other times in drawing comparisons between himself and his idol, the ever vigilant Walker, Texas Ranger.

Hernandez maintains a studio practice in Juneau, Alaska at The Canvas; work from his current series will be included in an upcoming group exhibition curated by Disparate Minds writers Tim Ortiz and Andreana Donahue, which will be on view at The Canvas’ exhibition space in December.

drawing in progress in the studio